United States Exploring Expedition: Difference between revisions

→Preparations: Hydrography Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 1 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.1) (Balon Greyjoy) |

||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

[[Alfred Thomas Agate]], engraver and illustrator, created an enduring record of traditional cultures such as the illustrations made of the dress and tattoo patterns of natives of the [[Ellice Islands]] (now [[Tuvalu]]).<ref>'Follow the Expedition', Volume 5, Chapter 2, pp. 35–75, 'Ellice's and Kingsmill's Group', http://www.sil.si.edu/DigitalCollections/usexex/</ref> |

[[Alfred Thomas Agate]], engraver and illustrator, created an enduring record of traditional cultures such as the illustrations made of the dress and tattoo patterns of natives of the [[Ellice Islands]] (now [[Tuvalu]]).<ref>'Follow the Expedition', Volume 5, Chapter 2, pp. 35–75, 'Ellice's and Kingsmill's Group', http://www.sil.si.edu/DigitalCollections/usexex/</ref> |

||

A collection of artifacts from the expedition also went to the [[National Institute for the Promotion of Science]], a precursor of the Smithsonian Institution. These joined artifacts from American history as the first artifacts in the Smithsonian collection.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://siarchives.si.edu/history/exhibits/baird/bairdb.htm |title=Planning a National Museum |publisher=Smithsonian Institution Archives |accessdate=January 2, 2010}}</ref> |

A collection of artifacts from the expedition also went to the [[National Institute for the Promotion of Science]], a precursor of the Smithsonian Institution. These joined artifacts from American history as the first artifacts in the Smithsonian collection.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://siarchives.si.edu/history/exhibits/baird/bairdb.htm |title=Planning a National Museum |publisher=Smithsonian Institution Archives |accessdate=January 2, 2010 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20090803084613/http://siarchives.si.edu//history/exhibits/baird/bairdb.htm |archivedate=August 3, 2009 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

||

==The expedition in popular culture== |

==The expedition in popular culture== |

||

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

* [[George F. Emmons|George Foster Emmons]] (1811–1884), lieutenant; {{USS |Peacock |1828 |6}}<ref name=Vincennes /><ref name=Peacock>http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/Crew/crew_display_by_ship.cfm?ship=Peacock</ref> |

* [[George F. Emmons|George Foster Emmons]] (1811–1884), lieutenant; {{USS |Peacock |1828 |6}}<ref name=Vincennes /><ref name=Peacock>http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/Crew/crew_display_by_ship.cfm?ship=Peacock</ref> |

||

* Dr. John L. Fox, ship's doctor; [[USS Vincennes (1826)|USS ''Vincennes'']]<ref name=Porpoise /><ref name=Vincennes /> |

* Dr. John L. Fox, ship's doctor; [[USS Vincennes (1826)|USS ''Vincennes'']]<ref name=Porpoise /><ref name=Vincennes /> |

||

* [[Charles Guillou]], ship's doctor; {{USS |Peacock |1828 |6}}<ref>{{cite web |title= Charles F. Guillou papers, 1838–1947 |publisher= The College of Physicians of Philadelphia |url= http://www.collphyphil.org/Site/FIND_AID/hist/histcfg1.htm |accessdate=March 4, 2011 }}</ref> |

* [[Charles Guillou]], ship's doctor; {{USS |Peacock |1828 |6}}<ref>{{cite web |title= Charles F. Guillou papers, 1838–1947 |publisher= The College of Physicians of Philadelphia |url= http://www.collphyphil.org/Site/FIND_AID/hist/histcfg1.htm |accessdate= March 4, 2011 }}{{dead link|date=December 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> |

||

* George Hammersly, midshipman;<ref name=Peacock /> |

* George Hammersly, midshipman;<ref name=Peacock /> |

||

* Silas Holmes; {{USS |Peacock |1828 |6}}<ref name=Peacock /> |

* Silas Holmes; {{USS |Peacock |1828 |6}}<ref name=Peacock /> |

||

| Line 396: | Line 396: | ||

** [https://www.history.navy.mil/search.html?q=Flying+Fish USS ''Flying Fish''] |

** [https://www.history.navy.mil/search.html?q=Flying+Fish USS ''Flying Fish''] |

||

** [https://www.history.navy.mil/search.html?q=USS+Sea+Gull USS ''Sea Gull''] |

** [https://www.history.navy.mil/search.html?q=USS+Sea+Gull USS ''Sea Gull''] |

||

*[http://www.museumsiskiyoutrail.org Museum of the Siskiyou Trail] |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20120415171721/http://www.museumsiskiyoutrail.org/ Museum of the Siskiyou Trail] |

||

{{Polar exploration|state=collapsed}} |

{{Polar exploration|state=collapsed}} |

||

Revision as of 14:31, 26 December 2017

United States Exploring Expedition

1. Hampton Roads; 2. Madeira; 3. Rio de Janeiro; 4. Tierra del Fuego; 5. Valparaíso; 6. Callao; 7. Samoa; 8. Fiji; 9. Sydney; 10. Antarctica; 11. Hawaii  1. Puget Sound; 2. Columbia; 3. San Francisco; 4. Polynesia; 5. Philippines; 6. Borneo; 7. Singapore; 8. Cape of Good Hope; 9. New York | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Fiji Samoa Tabiteuea | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Samoa: Malietoa Moli | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

2 sloops-of-war 1 ship 1 brig 2 schooners Marines and Sailors | unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

~30 killed or wounded 1 sloop-of-war sunk 1 schooner sunk[1] |

Fiji: ~80 killed or wounded Tabiteuea: 12 killed | ||||||

The United States Exploring Expedition was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States from 1838 to 1842. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones. Funding for the original expedition was requested by President John Quincy Adams in 1828, however, Congress would not implement funding until eight years later. In May 1836, the oceanic exploration voyage was finally authorized by Congress and created by President Andrew Jackson. The expedition is sometimes called the "U.S. Ex. Ex." for short, or the "Wilkes Expedition" in honor of its next appointed commanding officer, United States Navy Lieutenant Charles Wilkes. The expedition was of major importance to the growth of science in the United States, in particular the then-young field of oceanography. During the event, armed conflict between Pacific islanders and the expedition was common and dozens of natives were killed in action, as well as a few Americans.

Preparations

Through the lobbying efforts of Jeremiah N. Reynolds, the United States House of Representatives passed a resolution on 21 May 1828, requesting President John Quincy Adams to send a ship to explore the Pacific. Adams was keen on the resolution and ordered his Secretary of the Navy to ready a ship, the Peacock, while the House voted an appropriation in Dec. Yet, the bill stalled in the US Senate in Feb. 1829. However, under President Andrew Jackson, Congress passed legislation in 1836 approving the exploration mission. Yet again, the effort stalled under Secretary of the Navy Mahlon Dickerson until President Van Buren assumed office and pushed the effort forward.[2][3]

Originally, the expedition was under the command Commodore Jones, but he resigned in Nov. 1837, frustrated with all of the procrastination. Secretary of War Joel Roberts Poinsett, in April 1838, then assigned command to Wilkes, after more senior officers refused the command. Wilkes had a reputation for hydrography, geodesy, and magnetism. Additionally, Wilkes had received mathematics training from Nathaniel Bowditch, triangulation methods from Ferdinand Hassler, and geomagnetism from James Renwick.[2]: 19, 35, 56, 61

Personnel included naturalists, botanists, a mineralogist, a taxidermist, and a philologist. They were carried aboard the sloops-of-war USS Vincennes (780 tons), and USS Peacock (650 tons), the brig USS Porpoise (230 tons), the full-rigged ship Relief, which served as a store-ship, and two schooners, Sea Gull (110 tons) and USS Flying Fish (96 tons), which served as tenders.[2]: 43, 63, 65, 68, 73–76

On the afternoon of 18 August 1838, the vessels weighed anchor and set to sea under full sail. By 0730 the next morning, they had passed the lightship off Willoughby Spit and dischared the pilot. The fleet then headed to Madeira, taking advantage of the prevailing winds.[2]: 71–76

Coincidentally, Commodore George C. Read in command of the East India Squadron aboard the flagship frigate USS Columbia, together with the frigate USS John Adams, were at the time in the process of circumnavigating the globe when the ships paused for the second Sumatran punitive expedition, which required no detour.

Route of the expedition

Wilkes was to search for vigias, or shoals, as reported by John Purdy, but failed to corroborate those claims for the locations given. The squadron arrived in the Madeira Islands on 16 September 1838, and Porto Praya on 6 Oct.[2]: 86–87

The Peacock arrived at Rio de Janeiro on 21 Nov., and the Vincennes with brigs and schooners on 24 Nov. However, the Relief did not arrive until the 27th, setting a record for slowness, 100 days. While there, they used Enxados Island in Guanabara Bay for an observatory and naval yard for repair and refitting.[2]: 88–89

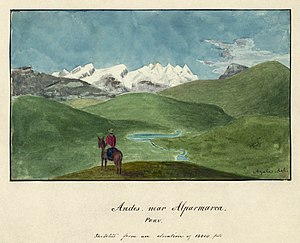

The Squadron did not leave Rio de Janeiro until 6 Jan. 1839, arriving at the mouth of the Río Negro on 25 Jan. On 19 Feb. the squadron joined the Relief, Flying Fish, and Sea Gull in Orange Harbor, Hoste Island, after passing through Le Maire Strait. While there, the expedition came in contact with the Fuegians. Wilkes sent an expedition south in an attempt to exceed Captain Cook's farthest point south, 71°10'. The Flying Fish reached 70° on 22 March, in the area about 100 miles north of Thurston Island, and what is now called Cape Flying Fish, and the Walker Mountains. The squadron joined the Peacock in Valparaiso on 10 May, but the Sea Gull was reported missing. On 6 June, the squadron arrived San Lorenzo, off Callao for repair and provisioning, while Wilkes dispatched the Relief homewards on 21 June.[2]: 91–96, 103–111

Leaving South America on 12 July, the expedition reached Reao of the Tuamotu Group on 13 Aug, and Tahiti on 11 Sept. They departed Tahiti on 10 Oct.[2]: 114–116, 123, 131

The expedition then visited Samoa and New South Wales, Australia. In December 1839, the expedition sailed from Sydney into the Antarctic Ocean and reported the discovery of the Antarctic continent on 16 Jan. 1840, when Henry Eld and William Reynolds aboard the Peacock sighted Eld Peak and Reynolds Peak along the George V Coast. On the 19 Jan., Reynolds spotted Cape Hudson. On 25 Jan., the Vincennes sighted the mountains behind the Cook Ice Shelf, similar peaks at Piner Bay on 30 Jan., and had covered 800 miles of coastline by 12 Feb., from 140° 30’ E. to 112° 16’ 12”E., when Wilkes acknowledged they had "discovered the Antarctic Continent." Named Wilkes Land, it includes Claire Land, Banzare Land, Sabrina Land, Budd Land, and Knox Land. They reached a westward goal of 105° E., the edge of Queen Mary Land, before departing to the north again on 21 Feb.[2]: 132, 142, 149, 155–159, 171–175

The Porpoise came across the French expedition of Jules Dumont d'Urville on 30 Jan. However, due to a misunderstanding of each other's intentions, the Porpoise and Astrolabe were unable to communicate.[2]: 176–177

In February 1840, some of the expedition were present at the initial signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in New Zealand.[4]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Some of the squadron then proceeded back to Sydney for repairs, while the rest visited the Bay of Islands, before arriving in Tonga in April. At Nuku'alofa the met King Josiah (Aleamotu'a), and the George (Taufa'ahau), chief of Ha'apai, before proceeding onwards to Fiji on 4 May. The Porpoise surveyed the Low Archipelago, while the Vincennes and Peacock proceeded onwards to Ovalau, where they signed a commercial treaty with Tanoa Visawaqa in Levuka. Edward Belcher's HMS Starling visited Ovalau at the same time.[2]: 180–182, 186–192, 195

Hudson was able to capture Vendovi, after holding his brothers Cocanauto, Qaraniqio, and Tui Dreketi (Roko Tui Dreketi or King of Rewa Province) hostage. Vendovi was deemed responsible for the attack against US sailors on Ono Island in 1836. Vendovi was to be taken back to the US after a brief trial onboard.[2]: 199–201

In July 1840, two members of the party, Lieutenant Underwood and Wilkes' nephew, Midshipman Wilkes Henry, were killed while bartering for food in western Fiji's Malolo Island. The cause of this event remains equivocal. Immediately prior to their deaths, the son of the local chief, who was being held as a hostage by the Americans, escaped by jumping out of the boat and running through the shallow water for shore. The Americans fired over his head. According to members of the expedition party on the boat, his escape was intended as a prearranged signal by the Fijians to attack. According to those on shore, the shooting actually precipitated the attack on the ground. The Americans landed sixty sailors to attack the hostile natives. Close to eighty Fijians were killed in the resulting American reprisal and two villages were burned to the ground.[1]

from "Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition." Philadelphia, 1845.

On 9 Aug., after three months of surveying, the squadron met off Macuata. The Vincennes and Peacock proceeded onwards to the Sandwich Islands, with the Flying Fish and Porpoise to meet them in Oahu by Oct. Along the way, Wilkes named the Phoenix Group. While in Hawaii, the officers were welcomed by Governor Kekuanaoa, King Kamehameha III, his aide William Richards, and the journalist James Jackson Jarves. The expedition surveyed Kauai, Oahu, Hawaii, and the peak of Mauna Loa. The Porpoise was dispatched in Nov. to survey several of the Tuamotus, including Aratika, Kauehi, Raraka, and Katiu, before proceeding onwards to Penrhyn and returning to Oahu on 24 March. On 5 April 1841, the squadron departed Honolulu, the Porpoise and Vincennes for the Pacific Northwest, the Peacock and Flying Fish to resurvey Samoa, before rejoining the squadron. Along the way, the Peacock and Flying Fish surveyed Jarvis Island, Enderbury Island, the Tokelau Islands, and Fakaofo. The Peacock followed this with surveys of the Tuvalu islands of Nukufetau, Vaitupu, and Nanumanga in March, followed by Tabiteuea in April. Also in April, the Peacock surveyed the Gilbert Islands of Nonouti, Aranuka, Maiana, Abemama, Kuria, Tarawa, Marakei, Butaritari, and Makin, before returning to Ohau on 13 June. The Peacock and Flying Fish then left for the Columbia River on 21 June.[2]: 212, 217, 219–221, 224–237, 240, 245–246

In April 1841, USS Peacock, under Lieutenant William L. Hudson, and USS Flying Fish, surveyed Drummond's Island, which was named for an American of the expedition. Lieutenant Hudson heard from a member of his crew that a ship had wrecked off the island and her crew massacred by the Gilbertese. A woman and her child were said to be the only survivors, so Hudson decided to land a small force of marines and sailors, under William M. Walker, to search the island. Initially, the natives were peaceful and the Americans were able to explore the island, without results. It was when the party was returning to their ship that Hudson noticed a member of his crew was missing. After making another search, the man was not found and the natives began arming themselves. Lieutenant Walker returned his force to the ship, to converse with Hudson, who ordered Walker to return to shore and demand the return of the sailor. Walker then reboarded his boats with his landing party and headed to shore. Walker shouted his demand and the natives charged for him, forcing the boats to turn back to the ships. It was decided on the next day that the Americans would bombard the hostiles and land again. While doing this, a force of around 700 Gilbertese warriors opposed the American assault, but were defeated after a long battle. No Americans were hurt, but twelve natives were killed and others were wounded, and two villages were also destroyed. A similar episode occurred two months before in February when the Peacock and the Flying Fish briefly bombarded the island of Upolu, Samoa following the death of an American merchant sailor on the island.[5]

The Vincennes and Porpoise reached Cape Disappointment on 28 April 1841, but then headed north to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Port Discovery, and Fort Nisqually, where they were welcomed by William Henry McNeill and Alexander Caulfield Anderson. The Porpoise surveyed the Admiralty Inlet, while boats from the Vincennes surveyed Hood Canal, and the coast northwards to the Fraser River. Wilkes visited Fort Clatsop, John McLoughlin at Fort Vancouver, and William Cannon on the Willamette River, while he sent Lt. Johnson on an expedition to Fort Okanogan, Fort Colvile and Fort Nez Perces, where they met Marcus Whitman.[2]: 253–256 Like his predecessor, British explorer George Vancouver, Wilkes spent a good deal of time near Bainbridge Island. He noted the bird-like shape of the harbor at Winslow and named it Eagle Harbor. Continuing his fascination with bird names, he named Bill Point and Wing Point. Port Madison, Washington and Points Monroe and Jefferson were named in honor of former United States presidents. Port Ludlow was assigned to honor Lieutenant Augustus Ludlow, who lost his life during the War of 1812.

The Peacock and Flying Fish arrived off Cape Disappointment on 17 July. However, the Peacock went aground while attempting to enter the Columbia River and was soon lost, though with no loss of life. The crew was able to lower six boats and get everyone into Baker's Bay, along with their journals, surveys, the chronometers, and some of Agate's sketches. A one-eyed Indian named George then guided the Flying Fish into the same bay. There, the crew set up "Peacockville", assisted by James Birnie of the Hudson's Bay Company, and the American Methodist Mission at Point Adams. They also traded with the local Clatsop and Chinookan Indians over the next three weeks, while surveying the channel, before journeying to Fort George and a reunion with the rest of the squadron. This prompted Wilkes to send the Vincennes to San Francisco Bay, while he continued to survey Grays Harbor.[2]: 247–253, 259

From the area of modern-day Portland, Oregon, Wilkes sent an overland party of 39 southwards, led by Emmons, but guided by Joseph Meek. The group included Agate, Eld, Colvocoresses, Brackenridge, Rich, Peale, Stearns, and Dana, and proceeded along an inland route to Fort Umpqua, Mount Shasta, the Sacramento River, John Sutter's New Helvetia, and then onwards to San Francisco Bay. They departed 7 Sept., and arrived aboard the Vincennes in Sausalito on 23 Oct., having traveled along the Siskiyou Trail.[2]: 259–265

Wilkes arrived with the Porpoise and Oregon, while the Flying Fish was to rendezvous with the squadron in Honolulu.[2]: 267 The squadron surveyed San Francisco and its tributaries, and later produced a map of "Upper California".[6]

The expedition then headed back out into the Pacific on 31 Oct., arriving Honolulu on 17 Nov., and departing on 28 Nov.[2]: 269–270, 272 They included a visit to Wake Island in 1841, and returned by way of the Philippines, the Sulu Archipelago, Borneo, Singapore, Polynesia and the Cape of Good Hope, reaching New York on June 10, 1842.

The expedition was plagued by poor relationships between Wilkes and his subordinate officers throughout. Wilkes' self-proclaimed status as captain and commodore, accompanied by the flying of the requisite pennant and the wearing of a captain's uniform while being commissioned only as a Lieutenant, rankled heavily with other members of the expedition of similar real rank. His apparent mistreatment of many of his subordinates, and indulgence in punishments such as "flogging round the fleet" resulted in a major controversy on his return to America.[1][2]: 219–220 Wilkes was court-martialled on his |return, but was acquitted on all charges except that of illegally punishing men in his squadron.

The publication program

For a short time Wilkes was attached to the Coast Survey, but from 1844 to 1861 he was chiefly engaged in preparing the report of the expedition. Twenty-eight volumes were planned, but only nineteen were published.[7] Of these, Wilkes wrote the multi-volume Narrative of the United States exploring expedition, during 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842[8] (consisting of an atlas and 5 volumes published in the fall of 1844),[1]: 338 Hydrography (consisting of an atlas published in 1858 and a volume published in 1861),[9][10][11] and Meteorology (consisting of a volume published in 1851).[12] The Narrative contains much interesting material concerning the manners and customs and political and economic conditions in many places then little known. Other valuable contributions were the three reports of James Dwight Dana on Zoophytes,[13] of 1846, Geology,[14] 1849, and Crustacea[15] of 1852 to 1854. In addition to many shorter articles and reports, Wilkes published the major scientific works Western America, including California and Oregon,[16] 1849, and Theory of the Winds[17] of 1856. The Smithsonian Institution digitized the five volume Narrative and the accompanying scientific volumes.[18] The mismanagement and bungling that plagued the expedition prior to its departure continued after its completion. By June 1848, many of the specimens had been lost or damaged and many remained unidentified. Asa Gray was hired for five years, including the first one being at the herbariums in Europe, to work on the botanical specimens.[3]: 185–190, 194–195

Significance of the expedition

The Wilkes Expedition played a major role in the development of 19th-century science, particularly in the growth of the American scientific establishment. Many of the species and other items found by the expedition helped form the basis of collections at the new Smithsonian Institution.[19]

With the help of the expedition's scientists, derisively called "clam diggers" and "bug catchers" by navy crew members, 280 islands, mostly in the Pacific, were explored, and over 800 miles of Oregon were mapped. Of no less importance, over 60,000 plant and bird specimens were collected. A staggering amount of data and specimens were collected during the expedition, including the seeds of 648 species, which were later traded, planted, and sent throughout the country. Dried specimens were sent to the National Herbarium, now a part of the Smithsonian Institution. There were also 254 live plants, which mostly came from the home stretch of the journey, that were placed in a newly constructed greenhouse in 1850, which later became the United States Botanic Garden.

Alfred Thomas Agate, engraver and illustrator, created an enduring record of traditional cultures such as the illustrations made of the dress and tattoo patterns of natives of the Ellice Islands (now Tuvalu).[20]

A collection of artifacts from the expedition also went to the National Institute for the Promotion of Science, a precursor of the Smithsonian Institution. These joined artifacts from American history as the first artifacts in the Smithsonian collection.[21]

The expedition in popular culture

The Wiki Coffin novels of Joan Druett are set on a fictional 7th ship accompanying the expedition.

Ships

- USS Vincennes, 780 tons, 18 guns, sloop-of-war, flagship

- USS Peacock, 650 tons, 22 guns, sloop-of-war

- USS Relief, 468 tons, 7 guns, full-rigged ship

- USS Porpoise, 230 tons, 10 guns, brig

- USS Sea Gull, 110 tons, 2 guns, schooner

- USS Flying Fish, 96 tons, 2 guns, schooner

- USS Oregon, formerly the Baltimore brig Thomas W. Perkins, purchased as a replacement for the Peacock[2]: 259

Members of the expedition

- James Alden[22] USS Vincennes[23]

- Thomas A. Budd, cartographer;

- Simon F. Blunt passed midshipman; USS Porpoise[22] USS Vincennes[23]

- Overton Carr USS Vincennes[23]

- Augustus Ludlow Case, lieutenant; USS Relief[24] USS Vincennes[23]

- George M. Colvocoresses (1816–1872), midshipman;[23]

- Henry Eld (1814–1850), midshipman;[25]

- Samuel B. Elliott, midshipman; USS Porpoise

- George Foster Emmons (1811–1884), lieutenant; USS Peacock[23][25]

- Dr. John L. Fox, ship's doctor; USS Vincennes[22][23]

- Charles Guillou, ship's doctor; USS Peacock[26]

- George Hammersly, midshipman;[25]

- Silas Holmes; USS Peacock[25]

- William L. Hudson, commanding officer; USS Peacock[25]

- Samuel R. Knox, commanding officer; USS Flying Fish

- A. K. Long, commanding officer; USS Relief[24]

- William Lewis Maury (1813–1878) USS Vincennes[23] USS Porpoise[22] USS Peacock[25]

- James W. E. Reid, commanding officer; USS Sea Gull

- William Reynolds (1815–1879),

- Cadwalader Ringgold (1802–1867), commanding officer; USS Porpoise[22]

- George T. Sinclair, sailing master; USS Porpoise[22]

- William Speiden (1797-1861), navy purser USS Peacock after whom Spieden Island was named;

- George M. Totten, midshipman, cartographer;USS Porpoise [22]

- Joseph Underwood, lieutenant, USS Vincennes[2]: 170

- Richard Russell Waldron, purser, USS Vincennes,[23] and special agent[27]

- Thomas W. Waldron, captain's clerk,[28] USS Porpoise[22][27]

- Charles Wilkes (1798–1877), commander of expedition

Engravers & Illustrators

- Alfred Thomas Agate (1812–1846), engraver and illustrator; USS Relief[24] USS Vincennes[23]

- Joseph Drayton (1795–1856), engraver and illustrator; USS Vincennes[29]

Scientific Corps

- William Dunlop Brackenridge (1810–1893), assistant botanist; USS Vincennes[29]

- Joseph Pitty Couthouy (1808–1864), conchologist; USS Vincennes

- James Dwight Dana (1813–1895), mineralogist and geologist; USS Peacock[22][23]

- F. L. Davenport, interpreter; USS Peacock[25]

- John W. W. Dyes, taxidermist;[2]: 76 USS Vincennes

- Horatio Emmons Hale (1817–1896), philologist; USS Peacock[25]

- Joseph Meek (1810–1875), Oregon guide

- Titian Ramsay Peale (1799–1885), naturalist; USS Peacock[25]

- Charles Pickering (1805–1878), naturalist;

- William Rich, botanist; USS Relief[29]

- Henry Wilkes

References

- ^ a b c d Philbrick, N., Sea of Glory, Viking, 2003

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Stanton, William (1975). The Great United States Exploring Expedition. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 13, 16–17, 23–24, 31, 33, 50–51. ISBN 0520025571.

- ^ a b Dupree, A. Hunter (1988). Asa Gray, American Botanist, Friend of Darwin. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 59–65. ISBN 978-0-801-83741-8.

- ^ Wilkes, Charles (1845). Narrative of the United States exploring expedition during the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. Vol. 2. Lea and Blanchard. p. 375.

...a disastrous circumstance for the natives...

- ^ Ellsworth, Harry A (1974). One Hundred Eighty Landings of United States Marines 1800–1934 (PDF). Hailer Publishing. p. 172–174. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- ^ Map of "Upper California"

- ^ The Publications of the U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1844–1874, Smithsonian Institution Libraries Digital Collection

- ^ http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007911158

- ^ http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/ScientificText/usexex19_34b.cfm?start=8

- ^ Hydrography in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- ^ Hartwell, Mary Ann, ed. (1911). Checklist of United States public documents 1789–1909. p. 661.

- ^ Meteorology / by Charles Wilkes; with twenty-five illustrations - Biodiverstiy Heritage Library

- ^ http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011619603

- ^ http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/ScientificText/USExEx19_14select.cfm

- ^ http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009027155

- ^ http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/006568406

- ^ http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/001486034

- ^ 'Follow the Expedition'

- ^ Adler, Antony (October 6, 2010). "From the Pacific to the Patent Office: The US Exploring Expedition and the origins of America's first national museum". Journal of the History of Collections.

- ^ 'Follow the Expedition', Volume 5, Chapter 2, pp. 35–75, 'Ellice's and Kingsmill's Group', http://www.sil.si.edu/DigitalCollections/usexex/

- ^ "Planning a National Museum". Smithsonian Institution Archives. Archived from the original on August 3, 2009. Retrieved January 2, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/Crew/crew_display_by_ship.cfm?ship=Porpoise

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/Crew/crew_display_by_ship.cfm?ship=Vincennes

- ^ a b c http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/Crew/crew_display_by_ship.cfm?ship=Relief

- ^ a b c d e f g h i http://www.sil.si.edu/digitalcollections/usexex/navigation/Crew/crew_display_by_ship.cfm?ship=Peacock

- ^ "Charles F. Guillou papers, 1838–1947". The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Retrieved March 4, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Domestic Intelligence – Exploring Squadron – List of officers and scientific corps". Army and Navy chronicle. 6: 142.

- ^ Edmond S. Meany, History of the State of Washington, (1909) pp.74–5 at Archive.org, accessed September 5, 2010

- ^ a b c SIarchives.si.edu

Further reading

- Bagley, Clarence B. (1957). History of King County, Washington. S. J. Clarke Publishing Company.* Barkan, Frances B. (1987). The Wilkes Expedition: Puget Sound and the Oregon Country. Washington State Capital Museum.

- Bertrand, Kenneth John (1971). Americans in Antarctica, 1775–1948. American Geographical Society.

- Borthwick, Doris Esch (1965). Outfitting the United States Exploring Expedition: Lieutenant Charles Wilkes' European assignment, August–November, 1836. Lancaster Press.

- Brokenshire, Doug (1993). Washington State Place Names: From Alki to Yelm. Caxton Press.

- Colvocoresses, George M. (1855). Four years in the government exploring expedition: Commanded by Captain Charles Wilkes, to the island of Madeira, Cape Verd Island, Brazil. J.M. Fairchild.

- Ellsworth, Harry A. (1974). One Hundred Eighty Landings of United States Marines 1800–1934. Washington D.C.: US Marines History and Museums Division.

- Goetzmann, William H. (1986). New Lands, New Men – America And The Second Great Age Of Discovery. Viking.

- Gurney, Alan (2000). The Race to the White Continent: Voyages to the Antarctic. Norton.

- Haskell, Daniel C. (1968). The United States Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842 and Its Publications 1844–1874. Greenwood Press.

- Haskett, Patrick J. (1974). The Wilkes Expedition in Puget Sound, 1841. State Capitol Museum.

- Henderson, Charles (1953). The Hidden Coasts: A Biography of Admiral Charles Wilkes. William Sloane Assoc.

- Jenkins, John S. (1856). Explorations and Adventures in and about the Pacific and Antarctic Oceans: Voyage of the U.S. Exploring Squadron, 1838–1842. New York: Hurst & Company.

- Jenkins, John S. (1853). United States Exploring Expeditions: Voyage of the U.S. Exploring Squadron. Kerr, Doughty & Lapham.

- Jenkins, John S. (1852). Voyage of the U.S. Exploring Squadron Commanded by Captain Charles Wilkes ... In 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841 and 1842. Alden, Beardsley & Co.

- Kruckeberg, Arthur R. (1995). The Natural History of Puget Sound Country. University of Washington Press.

- Mitterling, Philip I. (1957). America in the Antarctic to 1840.

- Morgan, Murray; Daniel Wilkes (1981). Puget's Sound: A Narrative of Early Tacoma and the Southern Sound. University of Washington Press.

- Perry, Fredi (2002). Bremerton and Puget Sound Navy Yard. Perry Publishing.

- Philbrick, Nathaniel (2003). Sea of Glory: America's Voyage of Discovery, the U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842. Viking Adult. ISBN 0-670-03231-X.

- Pickering, Charles (1863). The geographical distribution of animals and plants (United States exploring expedition, 1838–1842, under the command of Charles Wilkes). Trübner and Company.

- Poesch, Jessie Peale (1961). Titian Ramsay Peale And His Journals of The Wilkes Expedition, 1799–1885. American Philosophical Society.

- Reynolds, William; Nathaniel Philbrick (2004). The Private Journal of William Reynolds: United States Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842. Penguin Classics.

- Ritter, Harry (2003). Washington's History: The People, Land, and Events of the Far Northwest. Westwinds Press.

- Schwantes, Carlos Arnaldo (2000). The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History. University of Nebraska Press.

- Sellers, Charles Coleman (1980). Mr. Peale's Museum. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Stanton, William Ragan (1975). The Great United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842. University of California Press.

- Tyler, David B. (1968). The Wilkes Expedition: The First United States Exploring Expedition (1838–1842). American Philosophical Society.

- Viola, H.J. "The Wilkes Expedition on the Pacific Coast," Pacific Northwest Quarterly, January 1989.

- Viola, Herman J.; Carolyn Margolis (1985). Magnificent Voyagers: The U.S. Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842. Smithsonian.

- Wilkes, Charles (1851). Voyage round the world, Embracing the principal events of the narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition. G.P. Putnam.

- Charles Wilkes (1852). Narrative of the United States exploring expedition: during the years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842,. Vol. 2. Ingram, Cooke.

External links

- The United States Exploring Expedition, 1838–1842 — from the Smithsonian Institution Libraries Digital Collections

- Adrienne Kaeppler video on the Smithsonian Anthropology collections from the U.S. Exploring Expedition

- C-Span American History TV American Artifacts program on the U.S. Exploring Expedition, Part 1

- C-Span American History TV American Artifacts program on the U.S. Exploring Expedition, Part 2

- Material from the Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C.

- Museum of the Siskiyou Trail

- United States Exploring Expedition

- 1838 in the United States

- 1839 in Antarctica

- Artifacts in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution

- Circumnavigators of the globe

- Exploration of North America

- Explorers of the United States

- Global expeditions

- History of science and technology in the United States

- United States Navy in the 19th century

- Military expeditions of the United States

- Oceanography

- Pacific expeditions

- Pacific Ocean