Obelisk: Difference between revisions

KolbertBot (talk | contribs) m Bot: HTTP→HTTPS (v478) |

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 1 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.1) (Feminist) |

||

| Line 220: | Line 220: | ||

| [[Blantyre Monument]] || [[File:Monument near Bishopton - geograph.org.uk - 448575.jpg|100px]] || [[Erskine]], [[Renfrewshire]] || United Kingdom || {{convert|80|ft|m|disp=table|order=flip}} || align=center| ''circa'' 1825 || || <ref>{{cite web|url=http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/219026/details/erskine+house+blantyre+monument/|title=Site Record for Erskine House & Blantyre Monument|publisher=Canmore.rcahms.gov.uk|accessdate=2014-07-18}}</ref> |

| [[Blantyre Monument]] || [[File:Monument near Bishopton - geograph.org.uk - 448575.jpg|100px]] || [[Erskine]], [[Renfrewshire]] || United Kingdom || {{convert|80|ft|m|disp=table|order=flip}} || align=center| ''circa'' 1825 || || <ref>{{cite web|url=http://canmore.rcahms.gov.uk/en/site/219026/details/erskine+house+blantyre+monument/|title=Site Record for Erskine House & Blantyre Monument|publisher=Canmore.rcahms.gov.uk|accessdate=2014-07-18}}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Captain Cook's Monument || || Easby Moor, [[Great Ayton]], [[North Yorkshire]] || United Kingdom || {{convert|15.5|m|ft|disp=table}} || align=center| 1827 || || <ref>[http://www.hambleton.gov.uk/local_guide/display.htm?pk_localguide=37 Captain Cook's Monument<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

| Captain Cook's Monument || || Easby Moor, [[Great Ayton]], [[North Yorkshire]] || United Kingdom || {{convert|15.5|m|ft|disp=table}} || align=center| 1827 || || <ref>[http://www.hambleton.gov.uk/local_guide/display.htm?pk_localguide=37 Captain Cook's Monument<!-- Bot generated title -->]{{dead link|date=December 2017 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Groton Monument]] || [[File:GrotonMemorial.jpg|100px]] || [[Fort Griswold]], [[Groton, Connecticut]] || United States || {{convert|135|ft|m|disp=table|order=flip}} || align=center| 1830 || {{coord|41|21|18|N|72|4|46|W|type:landmark_region:US-CT|display=inline}} || <ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qy5ZXp__MuUC&pg=PA58&dq=Groton+Monument&hl=en&sa=X&ei=gpVDU_ilHIvQsQSEtIHQBw&ved=0CDkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Groton%20Monument&f=false | title=The Stone Records of Groton | publisher=Applewood Books | author=Caulkins, Francis | year=2010}}</ref> |

| [[Groton Monument]] || [[File:GrotonMemorial.jpg|100px]] || [[Fort Griswold]], [[Groton, Connecticut]] || United States || {{convert|135|ft|m|disp=table|order=flip}} || align=center| 1830 || {{coord|41|21|18|N|72|4|46|W|type:landmark_region:US-CT|display=inline}} || <ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Qy5ZXp__MuUC&pg=PA58&dq=Groton+Monument&hl=en&sa=X&ei=gpVDU_ilHIvQsQSEtIHQBw&ved=0CDkQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=Groton%20Monument&f=false | title=The Stone Records of Groton | publisher=Applewood Books | author=Caulkins, Francis | year=2010}}</ref> |

||

| Line 519: | Line 519: | ||

*[https://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http://www.geocities.com/mp_pollett/roma-co1.htm&date=2009-10-26+02:18:29 Obelisks in Rome] (Andrea Pollett) |

*[https://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http://www.geocities.com/mp_pollett/roma-co1.htm&date=2009-10-26+02:18:29 Obelisks in Rome] (Andrea Pollett) |

||

*[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/Europe/Italy/Lazio/Roma/Rome/_Texts/PLATOP*/obelisci.html Obelisks of Rome] (series of articles in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome) |

*[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/Europe/Italy/Lazio/Roma/Rome/_Texts/PLATOP*/obelisci.html Obelisks of Rome] (series of articles in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome) |

||

*[http://www.memo.fr/LieuAVisiter.asp?ID=VIS_FRA_ARL_036 History of the obelisk of Arles] (in French) |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20051014122437/http://www.memo.fr/LieuAVisiter.asp?ID=VIS_FRA_ARL_036 History of the obelisk of Arles] (in French) |

||

*[http://www.octavo.com/editions/ftaobc/index.html Octavo Edition of Domenico Fontana's book] depicting how he erected the Vatican obelisk in 1586. |

*[https://archive.is/20121209214626/http://www.octavo.com/editions/ftaobc/index.html Octavo Edition of Domenico Fontana's book] depicting how he erected the Vatican obelisk in 1586. |

||

* [http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/06/0628_caltechobelisk.html National Geographic: "Researchers Lift Obelisk With Kite to Test Theory on Ancient Pyramids"] |

* [http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2001/06/0628_caltechobelisk.html National Geographic: "Researchers Lift Obelisk With Kite to Test Theory on Ancient Pyramids"] |

||

*[http://cdm.reed.edu/ara-pacis/altar/related-material/obelisk-1/ Obelisk of Psametik II from Heliopolis, removed and reerected by Augustus in the northern Campus Martius, Rome] |

*[http://cdm.reed.edu/ara-pacis/altar/related-material/obelisk-1/ Obelisk of Psametik II from Heliopolis, removed and reerected by Augustus in the northern Campus Martius, Rome] |

||

Revision as of 20:45, 22 December 2017

An obelisk (UK: /ˈɒbəlɪsk/; US: /ˈɑːbəlɪsk/, from Ancient Greek: ὀβελίσκος obeliskos;[1][2] diminutive of ὀβελός obelos, "spit, nail, pointed pillar"[3]) is a tall, four-sided, narrow tapering monument which ends in a pyramid-like shape or pyramidion at the top. These were originally called tekhenu by their builders, the Ancient Egyptians. The Greeks who saw them used the Greek term 'obeliskos' to describe them, and this word passed into Latin and ultimately English.[4] Ancient obelisks are monolithic; that is, they consist of a single stone. Most modern obelisks are made of several stones; some, like the Washington Monument, are buildings.

The term stele is generally used for other monumental, upright, inscribed and sculpted stones.

Ancient obelisks

Egyptian

Obelisks were prominent in the architecture of the ancient Egyptians, who placed them in pairs at the entrance of temples. The word "obelisk" as used in English today is of Greek rather than Egyptian origin because Herodotus, the Greek traveller, was one of the first classical writers to describe the objects. A number of ancient Egyptian obelisks are known to have survived, plus the "Unfinished Obelisk" found partly hewn from its quarry at Aswan. These obelisks are now dispersed around the world, and fewer than half of them remain in Egypt.

The earliest temple obelisk still in its original position is the 68-foot (20.7 m) 120-metric-ton (130-short-ton)[5] red granite Obelisk of Senusret I of the XIIth Dynasty at Al-Matariyyah in modern Heliopolis.[6]

The obelisk symbolized the sun god Ra, and during the brief religious reformation of Akhenaten was said to be a petrified ray of the Aten, the sundisk. It was also thought that the god existed within the structure.

Benben was the mound that arose from the primordial waters Nu upon which the creator god Atum settled in the creation story of the Heliopolitan creation myth form of Ancient Egyptian religion. The Benben stone (also known as a pyramidion) is the top stone of the Egyptian pyramid. It is also related to the Obelisk.

It is hypothesized by New York University Egyptologist Patricia Blackwell Gary and Astronomy senior editor Richard Talcott that the shapes of the ancient Egyptian pyramid and obelisk were derived from natural phenomena associated with the sun (the sun-god Ra being the Egyptians' greatest deity).[7] The pyramid and obelisk might have been inspired by previously overlooked astronomical phenomena connected with sunrise and sunset: the zodiacal light and sun pillars respectively.

The Ancient Romans were strongly influenced by the obelisk form, to the extent that there are now more than twice as many obelisks standing in Rome as remain in Egypt. All fell after the Roman period except for the Vatican obelisk and were re-erected in different locations.

The largest standing and tallest Egyptian obelisk is the Lateran Obelisk in the square at the west side of the Lateran Basilica in Rome at 105.6 feet (32.2 m) tall and a weight of 455 metric tons (502 short tons).[8]

Not all the Egyptian obelisks in the Roman Empire were set up at Rome. Herod the Great imitated his Roman patrons and set up a red granite Egyptian obelisk in the hippodrome of his new city Caesarea in northern Judea. This one is about 40 feet (12 m) tall and weighs about 100 metric tons (110 short tons).[9] It was discovered by archaeologists and has been re-erected at its former site.

In Constantinople, the Eastern Emperor Theodosius shipped an obelisk in AD 390 and had it set up in his hippodrome, where it has weathered Crusaders and Seljuks and stands in the Hippodrome square in modern Istanbul. This one stood 95 feet (29 m) tall and weighing 380 metric tons (420 short tons). Its lower half reputedly also once stood in Istanbul but is now lost. The Istanbul obelisk is 65 feet (20 m) tall.[10]

Rome is the obelisk capital of the world.[citation needed] The most well-known is probably the 25 metres (82 ft), 331-metric-ton (365-short-ton) obelisk at Saint Peter's Square in Rome.[8] The obelisk had stood since AD 37 on its site on the wall of the Circus of Nero, flanking St Peter's Basilica:

- "The elder Pliny in his Natural History refers to the obelisk's transportation from Egypt to Rome by order of the Emperor Gaius (Caligula) as an outstanding event. The barge that carried it had a huge mast of fir wood which four men's arms could not encircle. One hundred and twenty bushels of lentils were needed for ballast. Having fulfilled its purpose, the gigantic vessel was no longer wanted. Therefore, filled with stones and cement, it was sunk to form the foundations of the foremost quay of the new harbour at Ostia."[11]

Re-erecting the obelisk had daunted even Michelangelo, but Sixtus V was determined to erect it in front of St Peter's, of which the nave was yet to be built. He had a full-sized wooden mock-up erected within months of his election. Domenico Fontana, the assistant of Giacomo Della Porta in the Basilica's construction, presented the Pope with a little model crane of wood and a heavy little obelisk of lead, which Sixtus himself was able to raise by turning a little winch with his finger. Fontana was given the project.

The obelisk, half-buried in the debris of the ages, was first excavated as it stood; then it took from 30 April to 17 May 1586 to move it on rollers to the Piazza: it required nearly 1000 men, 140 carthorses, and 47 cranes. The re-erection, scheduled for 14 September, the Feast of the Exaltation of the Cross, was watched by a large crowd. It was a famous feat of engineering, which made the reputation of Fontana, who detailed it in a book illustrated with copperplate etchings, Della Trasportatione dell'Obelisco Vaticano et delle Fabriche di Nostro Signore Papa Sisto V (1590),[12][13] which itself set a new standard in communicating technical information and influenced subsequent architectural publications by its meticulous precision.[14] Before being re-erected the obelisk was exorcised. It is said that Fontana had teams of relay horses to make his getaway if the enterprise failed. When Carlo Maderno came to build the Basilica's nave, he had to put the slightest kink in its axis, to line it precisely with the obelisk.

Three more obelisks were erected in Rome under Sixtus V: the one behind Santa Maria Maggiore (1587), the giant obelisk at the Lateran Basilica (1588), and the one at Piazza del Popolo (1589).[15]

An obelisk stands in front of the church of Trinità dei Monti, at the head of the Spanish Steps. Another obelisk in Rome is sculpted as carried on the back of an elephant. Rome lost one of its obelisks, the Boboli obelisk which had decorated the temple of Isis, where it was uncovered in the 16th century. The Medici claimed it for the Villa Medici, but in 1790 they moved it to the Boboli Gardens attached to the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, and left a replica in its stead.

Several more Egyptian obelisks have been re-erected elsewhere. The best-known examples outside Rome are the pair of 21-metre (69 ft) 187-metric-ton (206-short-ton) Cleopatra's Needles in London (21 metres or 69 feet) and New York City (21 metres or 70 feet) and the 23-metre (75 ft) 227-metric-ton (250-short-ton) obelisk at the Place de la Concorde in Paris.[16]

There are ancient Egyptian obelisks in the following locations:

- Egypt – 8

- Pharaoh Thutmosis I, Karnak Temple, Luxor

- Pharaoh Ramses II, Luxor Temple

- Pharaoh Hatshepsut, Karnak Temple, Luxor

- Pharaoh Senusret I, Al-Masalla area of Al-Matariyyah district in Heliopolis, Cairo

- Pharaoh Ramses III, Luxor Museum

- Pharaoh Ramses II, Gezira Island, Cairo, 20.4 m (67 ft)[17]

- Pharaoh Ramses II, Cairo International Airport, 16.97 m (55.7 ft)

- Pharaoh Seti II, Karnak Temple, Luxor, 7 m (23 ft)

- France – 1

- Pharaoh Ramses II, Luxor Obelisk, in Place de la Concorde, Paris

- Israel – 1

- Italy – 13 (includes the only one located in the Vatican City)

- Rome — 8 ancient Egyptian obelisks (see List of obelisks in Rome)

- Piazza del Duomo, Catania (Sicily)

- Benevento, two obelisks

- Boboli Obelisk (Florence)

- Urbino

- Poland – 1

- Turkey – 1

- Pharaoh Tuthmosis III, the Obelisk of Theodosius in the Hippodrome, Istanbul, along with the Byzantine Walled Obelisk and the Serpent Column

- United Kingdom – 4

- Pharaoh Tuthmosis III, "Cleopatra's Needle", on Victoria Embankment, London

- Pharaoh Amenhotep II, in the Oriental Museum, University of Durham

- Pharaoh Ptolemy IX, Philae obelisk, at Kingston Lacy, near Wimborne Minster, Dorset

- Pharaoh Nectanebo II, British Museum, London (pair of obelisks)

- United States – 1

- Pharaoh Tuthmosis III, "Cleopatra's Needle", in Central Park, New York

Assyrian

Obelisk monuments are also known from the Assyrian civilization, where they were erected as public monuments that commemorated the achievements of the Assyrian king.

The British Museum possesses four Assyrian obelisks:

The White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I (named due to its colour), was discovered by Hormuzd Rassam in 1853 at Nineveh. The obelisk was erected by either Ashurnasirpal I (1050–1031 BC) or Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC). The obelisk bears an inscription that refers to the king’s seizure of goods, people and herds, which he carried back to the city of Ashur. The reliefs of the Obelisk depict military campaigns, hunting, victory banquets and scenes of tribute bearing.

The Rassam Obelisk, named after its discoverer Hormuzd Rassam, was found on the citadel of Nimrud (ancient Kalhu). It was erected by Ashurnasirpal II, though only survives in fragments. The surviving parts of the reliefs depict scenes of tribute bearing to the king from Syria and the west.[19]

The Black Obelisk was discovered by Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1846 on the citadel of Kalhu. The obelisk was erected by Shalmaneser III and the reliefs depict scenes of tribute bearing as well as the depiction of two subdued rulers, Jehu the Israelite and Sua the Gilzanean, giving gestures of submission to the king. The reliefs on the obelisk have accompanying epigraphs, but besides these the obelisk also possesses a longer inscription that records one of the latest versions of Shalmaneser III’s annals, covering the period from his accessional year to his 33rd regnal year.

The Broken Obelisk, that was also discovered by Rassam at Nineveh. Only the top of this monolith has been reconstructed in the British Museum. The obelisk is the oldest recorded obelisk from Assyria, dating to the 11th century BC.[20]

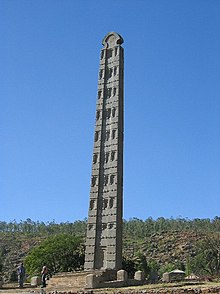

Axumite (Ethiopia)

A number of obelisks were carved in the ancient Axumite Kingdom of today northern Ethiopia. Together with (21-metre-high or 69-foot) King Ezana's Stele, the last erected one and the only unbroken, the most famous example of axumite obelisk is the so-called (24-metre-high or 79-footh) Obelisk of Axum. It was carved around the 4th century AD and, in the course of time, it collapsed and broke into three parts. In these conditions it was found by Italian soldiers in 1935, after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, looted and taken to Rome in 1937, where it stood in the Piazza di Porta Capena. Italy agreed in a 1947 UN agreement to return the obelisk but did not affirm its agreement until 1997, after years of pressure and various controversial settlements. In 2003 the Italian government made the first steps toward its return, and in 2008 it was finally re-erected.

The largest known obelisk, the Great Stele at Axum, now fallen, at 33 metres (108 ft) high and 3 m (9.8 ft) by 2 m (6 ft 7 in) at the base (520 metric tons or 570 short tons)[21] is one of the largest single pieces of stone ever worked in human history (the largest is either at Baalbek or the Ramesseum) and probably fell during erection or soon after, destroying a large part of the massive burial chamber underneath it. The obelisks, properly termed stelae or the native hawilt or hawilti as they do not end in a pyramid, were used to mark graves and underground burial chambers. The largest of the grave markers were for royal burial chambers and were decorated with multi-storey false windows and false doors, while nobility would have smaller less decorated ones. While there are only a few large ones standing, there are hundreds of smaller ones in "stelae fields".

Ancient Roman

The Romans commissioned obelisks in an ancient Egyptian style. Examples include:

- Arles, France —the Arles Obelisk, in Place de la République, a 4th-century obelisk of Roman origin

- Benevento, Italy — Roman obelisks[22][23]

- Munich — obelisk of Titus Sextius Africanus, Staatliches Museum Ägyptischer Kunst, Kunstareal, 1st century AD, 5.8 metres (19 ft)

- Rome — there are five ancient Roman obelisks in Rome. See List of obelisks in Rome.

Byzantine

- Walled Obelisk, Hippodrome of Constantinople. Built by Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (905–959) and originally covered with gilded bronze plaques.

Pre-Columbian

The prehistoric Tello Obelisk, found in 1919 at Chavín de Huantar in Peru, is a monolith stele with obelisk-like proportions. It was carved in a design of low relief with Chavín symbols, such as bands of teeth and animal heads. Long housed in the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú in Lima, it was relocated to the Museo Nacional de Chavín, which opened in July 2008. The obelisk was named for the archeologist Julio C. Tello, who discovered it and was considered the "father of Peruvian archeology." He was America's first indigenous archeologist.[24]

Modern obelisks

(Listed in date order)

17th century

| Obelisk name | Image | Location | Country | Elevation | Completed | Coordinates | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | ft | |||||||

| Fontaine des Quatre Dauphins |  |

Aix-en-Provence | France | 1667 | 43°31′35″N 5°26′44″E / 43.52639°N 5.44556°E | |||

18th century

| Obelisk name | Image | Location | Country | Elevation | Completed | Coordinates | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | ft | |||||||

| Market Square obelisk |  |

Ripon | United Kingdom | 24 | 80 | 1702 | The first large scale obelisk in Britain.[25] | |

| Stillorgan Obelisk |  |

Stillorgan, Dublin | Ireland | 30 | 100 | 1727 | ||

| St Luke Church |  |

London | United Kingdom | circa 1727–33 | spire by Nicholas Hawksmoor | |||

| Boyne Obelisk |  |

near Drogheda, County Louth | Ireland | 53 | 174 | 1736 | To commemorate William of Orange's victory at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 (destroyed in 1923, only the base remains). | |

| Conolly's Folly |  |

Celbridge, County Kildare | Ireland | 1740 | ||||

| Killiney Hill Obelisk |  |

Killiney, County Dublin | Ireland | 1742 | ||||

| Mamhead obelisk |  |

Mamhead | United Kingdom | 30 | 100 | 1742–1745 | An aid to shipping.[26] | |

| General Wolfe's Obelisk |  |

Stowe School, Buckinghamshire | United Kingdom | 1754 | ||||

| Montreal Park Obelisk | Riverhead, Sevenoaks, Kent | United Kingdom | 1761 | Lord Jeffery Amherst's Obelisk.[27] | ||||

| Kagul Obelisk |  |

Tsarskoe Selo | Russia | 1772 | ||||

| Chesma Obelisk |  |

Gatchina | Russia | 1775 | ||||

| Villa Medici |  |

Rome | Italy | 1790 | A 19th-century copy of the Egyptian obelisk moved to the Boboli Gardens in Florence | |||

| Obelisk Fountain |  |

James St., Dublin | Ireland | 1790 | ||||

| Constable Obelisk |  |

Gatchina Palace, Gatchina | Russia | 1793 | ||||

| Moore-Vallotton Incident marker | Wexford | Ireland | 1793 | [28] | ||||

| Rumyantsev Obelisk |  |

St Petersburg | Russia | 1799 | ||||

| Obelisk at Slottsbacken |  |

Stockholm | Sweden | 1800 | ||||

19th century

20th century

- ^a Unsure if this is actually an obelisk, rather than an antenna or spire

21st century

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2017) |

| Obelisk name | Image | Location | Country | Elevation | Completed | Coordinates | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m | ft | |||||||

| Capas National Shrine | File:The Obelisk at the Capas National Shrine.jpg | Tarlac province | Philippines | 70 | 230 | 2003 | 15°20′56″N 120°32′43″E / 15.34891°N 120.545246°E | [citation needed] |

| Kolonna Eterna |  |

San Gwann | Malta | 6 | 2003 | 35°54′35″N 14°28′36″E / 35.90972°N 14.47667°E | Egyptian obelisk by Paul Vella Critien[80] | |

| Colonna Mediterranea |  |

Luqa | Malta | 3.0 | 10 | 2006 | 35°51′38″N 14°29′3″E / 35.86056°N 14.48417°E | Abstract art by Paul Vella Critien[81] |

| Plaza Salcedo Obelisk |  |

Vigan, Ilocos Sur | Philippines | 17°34′N 120°23′E / 17.567°N 120.383°E | ||||

| Obelisco Novecento | Rome | Italy | 2004 | Sculpture by Arnaldo Pomodoro[citation needed] | ||||

| Cyclisk | Santa Rosa, California | United States | 20 | 65 | Made of 350 bicycles[citation needed] | |||

| Särkynyt lyhty | Tornio, Lapland | Finland | 9 | 30 | Made of stainless steel[citation needed] | |||

Erection experiments

In late summer 1999, Roger Hopkins and Mark Lehner teamed up with a NOVA (TV series) crew to erect a 25-ton obelisk. This was the third attempt to erect a 25-ton obelisk; the first two, in 1994 and 1999, ended in failure. There were also two successful attempts to raise a two-ton obelisk and a nine-ton obelisk. Finally in August–September 1999, after learning from their experiences, they were able to erect one successfully.

First Hopkins and Rais Abdel Aleem organized an experiment to tow a block of stone weighing about 25 tons. They prepared a path by embedding wooden rails into the ground and placing a sledge on them bearing a megalith weighing about 25 tons. Initially they used more than 100 people to try to tow it but were unable to budge it. Finally, with well over 130 people pulling at once and an additional dozen using levers to prod the sledge forward, they moved it. Over the course of a day, the workers towed it 10 to 20 feet. Despite problems with broken ropes, they proved the monument could be moved this way.[82] Additional experiments were done in Egypt and other locations to tow megalithic stone with ancient technologies, some of which are listed here.

One experiment was to transport a small obelisk on a barge in the Nile River. The barge was built based on ancient Egyptian designs. It had to be very wide to handle the obelisk, with a 2 to 1 ratio length to width, and it was at least twice as long as the obelisk. The obelisk was about 3.0 metres (10 ft) long and no more than 5 metric tons (5.5 short tons). A barge big enough to transport the largest Egyptian obelisks with this ratio would have had to be close to 61-metre-long (200 ft) and 30-metre-wide (100 ft). The workers used ropes that were wrapped around a guide that enabled them to pull away from the river while they were towing it onto the barge. The barge was successfully launched into the Nile.

The final and successful erection event was organized by Rick Brown, Hopkins, Lehner and Gregg Mullen in a Massachusetts quarry. The preparation work was done with modern technology, but experiments have proven that with enough time and people, it could have been done with ancient technology. To begin, the obelisk was lying on a gravel and stone ramp. A pit in the middle was filled with dry sand. Previous experiments showed that wet sand would not flow as well. The ramp was secured by stone walls. Men raised the obelisk by slowly removing the sand while three crews of men pulled on ropes to control its descent into the pit. The back wall was designed to guide the obelisk into its proper place. The obelisk had to catch a turning groove which would prevent it from sliding. They used brake ropes to prevent it from going too far. Such turning grooves had been found on the ancient pedestals. Gravity did most of the work until the final 15° had to be completed by pulling the obelisk forward. They used brake ropes again to make sure it did not fall forward. On 12 September they completed the project.[83]

This experiment has been used to explain how the obelisks may have been erected in Luxor and other locations. It seems to have been supported by a 3,000-year-old papyrus scroll in which one scribe taunts another to erect a monument for "thy lord". The scroll reads "Empty the space that has been filled with sand beneath the monument of thy Lord."[84] To erect the obelisks at Luxor with this method would have involved using over a million cubic meters of stone, mud brick and sand for both the ramp and the platform used to lower the obelisk.[85] The largest obelisk successfully erected in ancient times weighed 455 metric tons (502 short tons). A 520-metric-ton (570-short-ton) stele was found in Axum, but researchers believe it was broken while attempting to erect it.

See also

- List of megalithic sites

- List of pre-Columbian engineering projects in the Americas

- Monuments

- Benben Stone

- Phallic architecture

- Dagger (typography)

Notes

- ^ ὀβελίσκος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "obelisk". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ οβελός in Liddell and Scott.

- ^ Baker, Rosalie F.; Charles Baker (2001). Ancient Egyptians: People of the Pyramids. Oxford University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0195122213. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ "NOVA Online | Mysteries of the Nile | A World of Obelisks: Cairo". Pbs.org. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "OBELISK (Gr. b/3EXivrc... – Online Information article about OBELISK (Gr. b/3EXivrc..." Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ Patricia Blackwell Gary and Richard Talcott, "Stargazing in Ancient Egypt", Astronomy, June 2006, pp. 62–67.

- ^ a b "NOVA Online | Mysteries of the Nile | A World of Obelisks: Rome". Pbs.org. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "Caesarea Obelisk". Highskyblue.web.fc2.com. 18 June 2001. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "NOVA Online | Mysteries of the Nile | A World of Obelisks: Istanbul". Pbs.org. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ James Lees-Milne, Saint Peter's (1967).

- ^ Biblioteca Nacional Digital – Della trasportatione dell'obelisco Vaticano et delle fabriche di Nostro Signore Papa Sisto V, fatte dal caualier Domenico Fontana architetto di Sua Santita, In Roma, 1590

- ^ "Della trasportatione dell'obelisco vaticano et delle fabriche di nostro signore papa Sisto V fatte dal cavallier Domenico Fontana, architetto di Sva Santita, libro primo. – NYPL Digital Collections". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ "Martayan Lan Rare Books". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ "Della trasportatione dell'obel – Titelansicht – ETH-Bibliothek Zürich (NEBIS) – e-rara". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ "NOVA Online | Mysteries of the Nile | A World of Obelisks". Pbs.org. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ "History of the Egyptian Obelisks". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ "Obelisk of Ramesses II in the Museum's courtyard". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ British Museum Collection

- ^ "The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World" edited by Chris scarre 1999

- ^ "museodelsannio.com". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ Three Obelisks in Benevento

- ^ Richard L. Burger, Abstract of "The Life and Writings of Julio C. Tello", University of Iowa Press, accessed 27 September 2010

- ^ Barnes 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Fewins, Clive, And so to the tower, via the medieval treacle mines[permanent dead link] in The Independent dated 19 January 1997, at findarticles.com, accessed 19 July 2008

- ^ "English Heritage | English Heritage". Risk.english-heritage.org.uk. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ History of County Wexford: The Penal Laws & the 18th century

- ^ Richardson, Janet. "The Obelisk (Brightling Needle)". Geograph, Britain and Ireland. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ "Site Record for Erskine House & Blantyre Monument". Canmore.rcahms.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ Captain Cook's Monument[permanent dead link]

- ^ Caulkins, Francis (2010). The Stone Records of Groton. Applewood Books.

- ^ "Bunker Hill Monument". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Spencer Monument – Blata l-Bajda, Malta". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ "Jefferson's Gravestone". Retrieved 21 August 2015.

- ^ McAdam, Marika; Bainbridge, James (2013). "Iasi". Southeastern Europe. Lonely Planet.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help) - ^ "REGENT ROAD, CALTON OLD BURIAL GROUND AND MONUMENTS, INCLUDING SCREEN WALLS TO WATERLOO PLACE (Ref:27920)". Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ^ The Lansdowne Monument near to Cherhill, Wiltshire, Great Britain at geograph.org.uk, accessed 18 July 2008

- ^ Historic England. "Wellington Monument (1060281)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ^ Richards, Robin (2013). LE-JOG-ed: A mid-lifer’s trek from Land’s End to John O’Groats. Troubador Publishing. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-1-78306-935-4.

- ^ "Sewer Vent". NSW State Heritage Register. Office of Environment & Heritage, Government of New South Wales. 30 November 2001. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ "Lincoln Tomb". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Brigadier-General John Nicholson's Obelisk". www.azkhan.de. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Captain Cook`s Landing Site". Monument Australia. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Dauphin County Department of Military & Veterans' Affairs[dead link]

- ^ "13 Interesting Facts About the Washington Monument". I Hit The Button. 30 October 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 23 January 2007.

- ^ Vermont Historic Sites: Bennington Battle Monument

- ^ National Heritage Board (2002), Singapore's 100 Historic Places, Archipelago Press, ISBN 981-4068-23-3

- ^ http://www.dallasnews.com/s/dws/spe/2002/hiddenhistory/1850-1875/070002dnhhpioneer.442cf291.html

- ^ "Sergeant Floyd Monument". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Erekson, Keith A. (2005). "The Joseph Smith Memorial Monument and Royalton's 'Mormon Affair': Religion, Community, Memory, and Politics in Progressive Vermont" (PDF). Vermont History. 73: 117–51.

- ^ Kowsky, Francis R. (1981). "McKinley Monument". Buffalo architecture : a guide. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02172-2.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 13 March 2009.

- ^ "The Women's Monument entry in the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) Registry of Gazetted Sites, Objects and Shipwrecks". Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Walker, D. R. (26 January 2014). "The PAX Memorial in Walmer, Port Elizabeth". Blogging while allatsea. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ The City of Miami Beach. "Flagler Monument History" (PDF). The City of Miami Beach. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2006. Retrieved 13 June 2006.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Indiana World War Memorial Plaza Historic District". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Boer War Memorial". eMelbourne. July 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ^ Howard, A. "Forgotten Landscape: Soldiers Memorial Avenue". THRA Papers and Proceedings. 52 (2): 95–106.

- ^ "Big Red Apple". City of Cornellia. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "National Library of Australia - Trove Photograph - unveiling of monument to Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson, George Town".

- ^ "The War Memorial". Times of Malta. 23 June 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ San Jacinto Monument Fact Sheet

- ^ Paul Gervais Bell Jr., "Monumental Myths", Southwestern Historical Quarterly 103 (1999–2000) page before 1–14, p. 14.

- ^ "Maori Memorial. Obelisk on One Tree Hill. Scheme to divert fund". Auckland Star. 19 March 1931. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ Griffin, David J.; Pegum, Caroline (2000). Leinster House 1744 – 2000 An Architectural History. Dublin, Ireland: The Irish Architectural Archive in association with The Office of Public Works.

- ^ "1923 – Cenotaph, Leinster House, Dublin". Architecture of Dublin City & Lost Buildings of Ireland. Archiseek. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

- ^ Obelisco do Ibirapuera: Prefeitura e Estado unidos em prol do restauro Template:Pt icon

- ^ Ponce: Informacion para estudiantes. Archived 25 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine Government of the Autonomous Municipality of Ponce. Ponce, Puerto Rico. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ "Park Pobedy - a beautiful Victory memorial". Moscow Russia Insider's Guide. 2017. Archived from the original on 23 March 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Bayonet-Obelisk". Brest Hero-Fortress Memorial. 2013. Retrieved 19 January 2017.

- ^ "Trinity Site Monument". National Science Digital Library. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Geographic Centers". USGS Geography Products. U.S. Geological Survey. 2001. Retrieved 19 November 2009.

- ^ "Oregon Trail Monuments – Boise Arts & History". Boiseartsandhistory.org. Retrieved 20 July 2016.

- ^ "Oregon Trail Monuments". Boise City Department of Arts & History. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Na'aman, Ayelet (28 April 2009). "7 fascinating memorials". Ynetnews. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- ^ Seekins, Donald M. (2014). State and Society in Modern Rangoon. Routledge. pp. 36, 73. ISBN 9781317601548.

- ^ Guillaumier, Alfie (2005). Bliet u Rħula Maltin (in Maltese). Santa Venera: Klabb Kotba Maltin. p. 737. ISBN 99932-39-40-2.

- ^ Borg Cardona, Ben (2010), "Cars pass by Colonna Mediterranea, a sculpture by Malta artist Paul Vella Critien", abc.net.au.

- ^ "Dispatches", NOVA

- ^ "NOVA Online | Mysteries of the Nile | August 27, 1999: The Third Attempt". Pbs.org. 27 August 1999. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ NOVA (TV series) Secrets of Lost Empire II: "Pharaoh's Obelisks"

- ^ Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Ramses II: Magnificence on the Nile, New York: TIME/Life, 1993, pp. 56–57

References

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

Further reading

- Curran, Brian A., Anthony Grafton, Pamela O. Long, and Benjamin Weiss. Obelisk: A History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-262-51270-1.

- Chaney, Edward, "Roma Britannica and the Cultural Memory of Egypt: Lord Arundel and the Obelisk of Domitian", in Roma Britannica: Art Patronage and Cultural Exchange in Eighteenth-Century Rome, eds. D. Marshall, K. Wolfe and S. Russell, British School at Rome, 2011, pp. 147–70.

- Iversen, Erik, Obelisks in exile. Copenhagen, Vol. 1 1968, Vol. 2 1972

- Wirsching, Armin, Obelisken transportieren und aufrichten in Aegypten und in Rom. Norderstedt: Books on Demand 2007 (3rd ed. 2013), ISBN 978-3-8334-8513-8

External links

- Obelisk of the World (Shoji Okamoto)

- History of the Egyptian obelisks

- Obelisks in Rome (Andrea Pollett)

- Obelisks of Rome (series of articles in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome)

- History of the obelisk of Arles (in French)

- Octavo Edition of Domenico Fontana's book depicting how he erected the Vatican obelisk in 1586.

- National Geographic: "Researchers Lift Obelisk With Kite to Test Theory on Ancient Pyramids"

- Obelisk of Psametik II from Heliopolis, removed and reerected by Augustus in the northern Campus Martius, Rome