Iron-deficiency anemia: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 39.38.165.53 (talk) to last revision by Doc James. (TW) |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6.1) |

||

| Line 204: | Line 204: | ||

* [http://www.ironatlas.com/en.html/ Interactive material on Iron Metabolism] – From IronAtlas.com |

* [http://www.ironatlas.com/en.html/ Interactive material on Iron Metabolism] – From IronAtlas.com |

||

* [http://www.anaemiaworld.com/portal/eipf/pb/m/aw/establishing_the_cause_of_anemia Establishing the cause of anemia] – From AnaemiaWorld.com |

* [http://www.anaemiaworld.com/portal/eipf/pb/m/aw/establishing_the_cause_of_anemia Establishing the cause of anemia] – From AnaemiaWorld.com |

||

* [http://www.anemia.org/patients/information-handouts/iron-deficiency/ Handout: Iron Deficiency Anemia] – From the National Anemia Action Council |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20080917200428/http://www.anemia.org/patients/information-handouts/iron-deficiency/ Handout: Iron Deficiency Anemia] – From the National Anemia Action Council |

||

* [http://www.nps.org.au/health_professionals/publications/nps_news/current/iron_anaemia NPS News 70: Iron deficiency anaemia: NPS – Better choices, Better health] – From the National Prescribing Service |

* [http://www.nps.org.au/health_professionals/publications/nps_news/current/iron_anaemia NPS News 70: Iron deficiency anaemia: NPS – Better choices, Better health] – From the National Prescribing Service |

||

Revision as of 18:04, 16 November 2017

| Iron-deficiency anemia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Iron-deficiency anaemia |

| |

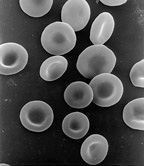

| Red blood cells | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | Feeling tired, weakness, shortness of breath, confusion, pallor[1] |

| Complications | Heart failure, arrhythmias, frequent infections[2] |

| Causes | Iron deficiency[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Blood tests[4] |

| Treatment | Dietary changes, medications, surgery[3] |

| Medication | Iron supplements, vitamin C, blood transfusions[5] |

| Frequency | 1.48 billion (2015)[6] |

| Deaths | 54,200 (2015)[7] |

Iron-deficiency anemia is anemia caused by a lack of iron.[3] Anemia is defined as a decrease in the number of red blood cells or the amount of hemoglobin in the blood.[8][3] When onset is slow, symptoms are often vague including feeling tired, weakness, shortness of breath, or poor ability to exercise.[1] Anemia that comes on quickly often has greater symptoms including: confusion, feeling like one is going to pass out, and increased thirst.[1] There needs to be significant anemia before a person becomes noticeably pale.[1] Problems with growth and development may occur in children.[3] There may be additional symptoms depending on the underlying cause.[1]

Iron-deficiency anemia is usually caused by blood loss, insufficient dietary intake, or poor absorption of iron from food.[3] Sources of blood loss can include heavy periods, childbirth, uterine fibroids, stomach ulcers, colon cancer, and urinary tract bleeding.[9] A poor ability to absorb iron may occur as a result of Crohn's disease or a gastric bypass.[9] In the developing world parasitic worms, malaria, and HIV/AIDS increase the risk.[10] Diagnosis is generally confirmed by blood tests.[4]

Prevention is by eating a diet high in iron or iron supplementation in those at risk.[11] Treatment depends on the underlying cause and may include dietary changes, medications, or surgery.[3] Iron supplements and vitamin C may be recommended.[5] Severe cases may be treated with blood transfusions or iron injections.[3]

Iron-deficiency anemia affected about 1.48 billion people in 2015.[6] A lack of dietary iron is estimated to cause approximately half of all anemia cases globally.[12] Women and young children are most commonly affected.[3] In 2015 anemia due to iron deficiency resulted in about 54,000 deaths – down from 213,000 deaths in 1990.[13][7]

Signs and symptoms

Iron-deficiency anemia is characterized by the sign of pallor (reduced oxyhemoglobin in skin or mucous membranes), and the symptoms of fatigue, lightheadedness, and weakness. None of the symptoms (or any of the others below) are sensitive or specific. Pallor of mucous membranes (primarily the conjunctiva) in children indicates anemia with the best correlation to the actual disease, but in a large study was found to be only 28% sensitive and 87% specific (with high predictive value) in distinguishing children with anemia [hemoglobin (Hb) <11.0 g/dl] and 49% sensitive and 79% specific in distinguishing severe anemia (Hb < 7.0 g/dl).[14] Thus, this sign is reasonably predictive when present, but not helpful when absent, as only one-third to one-half of children who are anemic (depending on severity) will show pallor. Iron-deficiency must be diagnosed by laboratory testing.

Because iron deficiency tends to develop slowly, adaptation occurs and the disease often goes unrecognized for some time, even years; patients often adapt to the systemic effects that anemia causes. In severe cases, dyspnea (trouble breathing) can occur. Unusual obsessive food cravings, known as pica, may develop. Pagophagia or pica for ice has been suggested to be specific, but is actually neither a specific or sensitive symptom, and is not helpful in diagnosis. When present, it may (or may not) disappear with correction of iron-deficiency anemia.

Other symptoms and signs of iron-deficiency anemia include:

Infant development

Iron-deficiency anemia for infants in their earlier stages of development may have greater consequences than it does for adults. An infant made severely iron-deficient during its earlier life cannot recover to normal iron levels even with iron therapy. In contrast, iron deficiency during later stages of development can be compensated with sufficient iron supplements. Iron-deficiency anemia affects neurological development by decreasing learning ability, altering motor functions, and permanently reducing the number of dopamine receptors and serotonin levels. Iron deficiency during development can lead to reduced myelination of the spinal cord, as well as a change in myelin composition. Additionally, iron-deficiency anemia has a negative effect on physical growth. Growth hormone secretion is related to serum transferrin levels, suggesting a positive correlation between iron-transferrin levels and an increase in height and weight. This is also linked to pica, as it can be a cause.

Cause

A diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia then requires further investigation as to its cause. It can be caused by increased iron demand / loss or decreased iron intake,[16] and can occur in both children and adults. The cause of chronic blood loss should all be considered, according to the patient's sex, age, and history, and anemia without an attributable underlying cause is sufficient for an urgent referral to exclude underlying malignancy. In babies and adolescents, rapid growth may outpace dietary intake of iron, and result in deficiency without disease or grossly abnormal diet.[16] In women of childbearing age, heavy or long menstrual periods can also cause mild iron-deficiency anemia.

Parasitic disease

The leading cause of iron deficiency worldwide is a parasitic disease known as a helminthiasis caused by infestation with parasitic worms (helminths) such as tapeworms, flukes, and roundworms.[citation needed] The World Health Organization estimates that "approximately two billion people are infected with soil-transmitted helminths worldwide."[17] Parasitic worms cause both inflammation and chronic blood loss.

Blood loss

Blood contains iron within red blood cells, so blood loss leads to a loss of iron. There are several common causes of blood loss: Women with menorrhagia (heavy menstrual periods) are at risk of iron-deficiency anemia because they are at higher-than-normal risk of losing a larger amount blood during menstruation than is replaced in their diet. Slow, chronic blood loss within the body — such as from a peptic ulcer, angiodysplasia, a colon polyp or gastrointestinal cancer, excessively heavy periods — can cause iron-deficiency anemia. Gastrointestinal bleeding can result from regular use of some groups of medication, such as NSAIDs (e.g. aspirin), anticoagulants such as clopidogrel and warfarin, although these are required in some patients, especially those with states causing thrombophilia.

Diet

The body normally gets the iron it requires from foods. If a person consumes too little iron, or iron that is poorly absorbed (non-heme iron), they can become iron deficient over time. Examples of iron-rich foods include meat, eggs, leafy green vegetables and iron-fortified foods. For proper growth and development, infants and children need iron from their diet, too.[18] A high intake of cow’s milk is associated with an increased risk of iron deficiency anemia.[19] Other risk factors for iron deficiency include low meat intake and low intake of iron-fortified products.[19]

Iron absorption

Iron from food is absorbed into the bloodstream in the small intestine, especially the duodenum and proximal ileum. Many intestinal disorders can reduce the body's ability to absorb iron. There are different mechanisms that may be present.

In cases where there has been a reduction in surface area of the bowel, such as in celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease or post-surgical resection, the body can absorb iron, but there is simply insufficient surface area.[citation needed]

If there is insufficient production of hydrochloric acid in the stomach, hypochlorhydria/achlorhydria can occur (often due to chronic H. pylori infections or long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy). Ferrous and ferric iron salts will precipitate out of solution in the bowel and be poorly absorbed.

In cases where systemic inflammation is present, iron will be absorbed into enterocytes but, due to the reduction in basolateral ferroportin molecules which allow iron to pass into the systemic circulation, iron is trapped in the enterocytes and is lost from the body when the enterocytes are sloughed off. Depending on the disease state, one or more mechanisms may occur.[citation needed]

Pregnancy

Without iron supplementation, iron deficiency anemia occurs in many pregnant women because their iron stores need to serve their own increased blood volume as well as be a source of hemoglobin for the growing fetus, and for placental development.[18]

Other less common causes are intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria.

Mechanism

Anemia is one result of significant iron deficiency. When the body has sufficient iron to meet its needs (functional iron), the remainder is stored for later use in all cells, but mostly in the bone marrow, liver, and spleen. These stores are called ferritin complexes and are part of the human (and other animals) iron metabolism systems. Ferritin complexes in humans carry about 4500 iron atoms and form into 24 protein subunits of two different types.[20]

Diagnosis

History

Anemia may be diagnosed from symptoms and signs, but when it is mild, it may not be diagnosed from mild nonspecific symptoms.

The diagnosis of iron-deficiency anemia will be suggested by appropriate history (e.g., anemia in a menstruating woman or an athlete engaged in long-distance running), the presence of occult blood (i.e., hidden blood) in the stool, and often by additional history.[21] For example, known celiac disease can cause malabsorption of iron. A travel history to areas in which hookworms and whipworms are endemic may be helpful in guiding certain stool tests for parasites or their eggs.[citation needed]

Blood tests

| Change | Parameter |

|---|---|

| ↓ | ferritin, hemoglobin, MCV |

| ↑ | TIBC, transferrin, RDW |

Anemia is often first shown by routine blood tests, which generally include a complete blood count (CBC) which is performed by an instrument which gives an output as a series of index numbers. A sufficiently low hemoglobin (Hb) by definition makes the diagnosis of anemia, and a low hematocrit value is also characteristic of anemia. Further studies will be undertaken to determine the anemia's cause. If the anemia is due to iron deficiency, one of the first abnormal values to be noted on a CBC, as the body's iron stores begin to be depleted, will be a high red blood cell distribution width (RDW), reflecting an increased variability in the size of red blood cells (RBCs). In the course of slowly depleted iron status, an increasing RDW normally appears even before anemia appears.

A low mean corpuscular volume (MCV) often appears next during the course of body iron depletion. It corresponds to a high number of abnormally small red blood cells. A low MCV, a low mean corpuscular hemoglobin or mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, and the appearance of the RBCs on visual examination of a peripheral blood smear narrows the problem to a microcytic anemia (literally, a "small red blood cell" anemia). The numerical values for these measures are all calculated by modern laboratory equipment.

The blood smear of a person with iron deficiency shows many hypochromic (pale and relatively colorless) and rather small RBCs, and may also show poikilocytosis (variation in shape) and anisocytosis (variation in size). With more severe iron-deficiency anemia, the peripheral blood smear may show hypochromic pencil-shaped cells, and occasionally small numbers of nucleated red blood cells.[22] Very commonly, the platelet count is slightly above the high limit of normal in iron deficiency anemia (this is mild thrombocytosis). This effect was classically postulated to be due to high erythropoietin levels in the body as a result of anemia, cross-reacting to activate thrombopoietin receptors in the precursor cells that make platelets; however, this process has not been corroborated. Such slightly increased platelet counts present no danger, but remain valuable as an indicator even if their origin is not yet known.[citation needed]

Body-store iron deficiency is diagnosed by tests such as a low serum ferritin, a low serum iron level, an elevated serum transferrin and a high total iron binding capacity. A low serum ferritin is the most sensitive lab test for iron deficiency anemia. However, serum ferritin can be elevated by any type of chronic inflammation and so is not always a reliable test of iron status if it is within normal limits (i.e. this test is meaningful if abnormally low, but less meaningful if normal).

Serum iron levels (i.e. iron not part of the hemoglobin in red cells) may be measured directly in the blood, but these levels increase immediately with iron supplementation (the patient must stop supplements for 24 hours), and pure blood-serum iron concentration, in any case, is not as sensitive as a combination of total serum iron, along with a measure of the serum iron-binding protein levels (TIBC). The ratio of serum iron to TIBC (called iron saturation or transferrin saturation index or percent) is the most specific indicator of iron deficiency when it is sufficiently low. The iron saturation (or transferrin saturation) of < 5% almost always indicates iron deficiency, while levels from 5% to 10% make the diagnosis of iron deficiency possible but not definitive. A transferrin saturation of 12% or more (taken alone) makes the diagnosis unlikely. Normal saturations are usually slightly lower for women (>12%) than for men (>15%), but this may indicate simply an overall slightly poorer iron status for women in the "normal" population.[citation needed]

Iron-deficiency anemia and thalassemia minor present with many of the same lab results. It is very important not to treat a people with thalassemia with an iron supplement, as this can lead to hemochromatosis (accumulation of iron in various organs, especially the liver). A hemoglobin electrophoresis provides useful evidence for distinguishing these two conditions, along with iron studies.[citation needed]

Screening

It is unclear if screening pregnant women for iron deficiency during pregnancy improves outcomes in the developing world.[23]

Gold standard

Conventionally, a definitive diagnosis requires a demonstration of depleted body iron stores obtained by bone marrow aspiration, with the marrow stained for iron.[24][25] Because this is invasive and painful, while a clinical trial of iron supplementation is inexpensive and not traumatic, patients are often treated based on clinical history and serum ferritin levels without a bone marrow biopsy. Furthermore, a study published April 2009[26] questions the value of stainable bone marrow iron following parenteral iron therapy.

Treatment

This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (July 2016) |  |

Anemia is sometimes treatable, but certain types of anemia may be lifelong. If the cause is a dietary iron deficiency, eating more iron-rich foods, such as beans, lentils or red meat, or taking iron supplements will usually correct the anemia. Alternatively, intravenous iron (or blood transfusions) can be administered.

The difference between iron intake and iron absorption, also known as bioavailability, can be great. Iron absorption problems are worsened when iron is taken in conjunction with milk, tea, coffee and other substances. A number of methods that can help mitigate this, including:

- Fortification with ascorbic acid increases bioavailability in both presence and absence of inhibiting substances, but is subject to deterioration from moisture or heat. Ascorbic acid fortification is usually limited to sealed, dried foods, but individuals can easily take ascorbic acid with a basic iron supplement for the same benefits. The primary benefit over ascorbic acid is durability and shelf life, particularly for products like milk, which undergo heat treatment.

- Microencapsulation with lecithin binds and protects the iron particles from the action of inhibiting substances.

- Using an iron amino acid chelate, such as NaFeEDTA, similarly binds and protects the iron particles. A study by the hematology unit of the University of Chile indicated chelated iron (ferrous bis-glycine chelate) can work with ascorbic acid to achieve even higher absorption levels.

- Separating intake of iron and inhibiting substances by a few hours

- Using nondairy milk (such as soy, rice, or almond milk) or goats' milk instead of cows' milk

- Gluten-free diets can resolve some instances of iron-deficiency anemia if it is a result of celiac disease.

- Heme iron, found only in animal foods, such as meat, fish, and poultry, is more easily absorbed than nonheme iron, found in plant foods and supplements.[27][28]

Iron bioavailability comparisons require stringent controls because the largest factor affecting bioavailability is the subject's existing iron level. Informal studies on bioavailability usually do not take this factor into account, so exaggerated claims from health supplement companies based on this sort of evidence should be ignored. Scientific studies are still in progress to determine which approaches yield the best results and the lowest costs.

If anemia does not respond to oral treatments, it may be necessary to administer iron parenterally using a drip or hemodialysis. Parenteral iron involves risks of fever, chills, backache, myalgia, dizziness, syncope, rash, and with some preparations, anaphylactic shock. The total incidence of adverse events is much lower than that with oral tablets (where the dose needs to be reduced or treatment stopped in over 40% of subjects) and blood transfusions.

A follow-up blood test is important to demonstrate whether the treatment has been effective; it can be undertaken after two to four weeks. With oral iron, this usually requires a delay of three months for tablets to have a significant effect.

Iron replacement

When adjusting daily iron supplementation regimens, lowering the daily iron dose requires a longer duration of therapy. The estimated total dose of elemental iron may be used to guide therapy, and replacement may be provided in cycles. Based on this approach, the person should participate in their own care by determining the iron formulation and dose schedule that they are able to tolerate. The amount of elemental iron that is absorbed in the gut is not constant, and can change significantly depending on several factors, including hemoglobin level and body iron stores. The amount of iron absorbed decreases as the iron deficiency is corrected. Therefore, it is not possible to predict the exact amount of iron that will be absorbed, but it is recommended that approximately 10%-20% of an oral iron dose will be absorbed in the beginning of the therapy.

For ferrous sulfate, one cycle consists of 75 pills or three pills daily for 25 days. Among people with moderate levels of anemia, a single cycle of should be enough and partial replacement of iron stores. If the anemia is not severe and there is no complicating feature such as ongoing blood loss or enteropathies, additional iron supplementation cycles are not going to be required for correcting the anemia. Re-evaluation of the anemia after completion of the first cycle should be performed to see if additional iron supplementation is necessary. If a person is predicted to have ongoing iron deficits (e.g. menorrhagia), maintenance dosing of iron supplements can easily be devised. The key feature of the cycled dosing strategy proposed here is that several factors including the cause of iron deficiency Anemia, the total iron deficit, replacement iron formulations, and the predicted duration of replacement therapy are integrated for implementation of an individualized therapeutic plan.[29]

Epidemiology

A moderate degree of iron-deficiency anemia affects approximately 610 million people worldwide or 8.8% of the population.[31] It is slightly more common in female (9.9%) than males (7.8%).[31] Mild iron deficiency anemia affects another 375 million.[31]

Within the U.S iron-deficiency anemia affects about 2% of adult males, 10.5% of Caucasian women, and 20% of African-American and Mexican-American women.[32]

References

- ^ a b c d e Janz, TG; Johnson, RL; Rubenstein, SD (Nov 2013). "Anemia in the Emergency Department: Evaluation and Treatment". Emergency Medicine Practice. 15 (11): 1–15, quiz 15-6. PMID 24716235.

- ^ "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Iron-Deficiency Anemia?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i "What Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia? - NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "How Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia Diagnosed?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 15 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "How Is Iron-Deficiency Anemia Treated?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. PMID 27733282.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. PMID 27733281.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Stedman's Medical Dictionary (28th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. p. Anemia. ISBN 9780781733908.

- ^ a b "What Causes Iron-Deficiency Anemia?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Micronutrient deficiencies". WHO. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "How Can Iron-Deficiency Anemia Be Prevented?". NHLBI. 26 March 2014. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Combs, Gerald F. (2012). The Vitamins. Academic Press. p. 477. ISBN 9780123819802. Archived from the original on 2017-08-18.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators (17 December 2014). "Global, Regional, and National Age-Sex Specific All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality for 240 Causes of Death, 1990-2013: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

{{cite journal}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-07-12. Retrieved 2012-05-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Pallor in diagnosis of iron deficiency in children - ^ Rangarajan, Sunad; D'Souza, George Albert. (April 2007). "Restless legs syndrome in Indian patients having iron deficiency anemia in a tertiary care hospital". Sleep Medicine. 8 (3): 247–51. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2006.10.004. PMID 17368978.

- ^ a b "NPS News 70: Iron deficiency anaemia". NPS Medicines Wise. October 1, 2010. Archived from the original on February 22, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) World Health Organization Fact Sheet No. 366, Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections, updated June 2013 - ^ a b "Iron deficiency anemia". Mayo Clinic. March 4, 2011. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Decsi, T.; Lohner, S. (2014). "Gaps in meeting nutrient needs in healthy toddlers". Ann Nutr Metab. 65 (1): 22–8. doi:10.1159/000365795. PMID 25227596.

- ^ Handout: Iron Deficiency Anemia Archived 2008-09-17 at the Wayback Machine – National Anemia Action Council

- ^ Brady PG (October 2007). "Iron deficiency anemia: a call for". Southern Medical Journal. 100 (10): 966–967. doi:10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181520699. PMID 17943034. Retrieved July 23, 2012.

- ^ Stephen J. McPhee, Maxine A. Papadakis. Current medical diagnosis and treatment 2009 page.428

- ^ Siu, AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force (6 October 2015). "Screening for Iron Deficiency Anemia and Iron Supplementation in Pregnant Women to Improve Maternal Health and Birth Outcomes: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 163 (7): 529–36. doi:10.7326/m15-1707. PMID 26344176.

- ^ Mazza, J.; Barr, R. M.; McDonald, J. W.; Valberg, L. S. (21 October 1978). "Usefulness of the serum ferritin concentration in the detection of iron deficiency in a general hospital". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 119 (8): 884–886. PMC 1819106. PMID 737638. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kis, AM; Carnes, M (July 1998). "Detecting Iron Deficiency in Anemic Patients with Concomitant Medical Problems". J Gen Intern Med. 13 (7): 455–61. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00134.x. PMC 1496985. PMID 9686711.

- ^ Thomason, Ronald W.; Almiski, Muhamad S. (April 2009). "Evidence That Stainable Bone Marrow Iron Following Parenteral Iron Therapy Does Not Correlate With Serum Iron Studies and May Not Represent Readily Available Storage Iron". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 131 (4): 580–585. doi:10.1309/AJCPBAY9KRZF8NUC. PMID 19289594. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ National Institutes of Health. "Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Iron". United States of America, Department of Health and Human Services. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Miret, Silvia; Simpson, Robert J.; McKie, Andrew T. (1 July 2003). "Physiology and molecular biology of dietary iron absorption". Annual Review of Nutrition. 23 (1): 283–301. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073139.

- ^ Alleyne, Michael; Horne, McDonald K.; Miller, Jeffery L. (1 November 2008). "Individualized treatment for iron-deficiency anemia in adults". The American Journal of Medicine. 121 (11): 943–948. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.07.012. ISSN 0002-9343. PMC 2582401. PMID 18954837.

- ^ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2002". World Health Organization. 2002. Archived from the original (xls) on 2013-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Vos, T; Flaxman, AD; Naghavi, M; Lozano, R; Michaud, C; Ezzati, M; Shibuya, K; Salomon, JA; et al. (Dec 15, 2012). "Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) for 1160 Sequelae of 289 Diseases and Injuries 1990-2010: a Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2163–96. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. PMID 23245607.

- ^ Killip, S; Bennett, JM; Chambers, MD (1 March 2007). "Iron deficiency anemia". American family physician. 75 (5): 671–8. PMID 17375513. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- The Importance of Iron – From IronTherapy.Org

- Interactive material on Iron Metabolism – From IronAtlas.com

- Establishing the cause of anemia – From AnaemiaWorld.com

- Handout: Iron Deficiency Anemia – From the National Anemia Action Council

- NPS News 70: Iron deficiency anaemia: NPS – Better choices, Better health – From the National Prescribing Service