Philosophy: Difference between revisions

Infogiraffic (talk | contribs) WP:ATC |

Section "Historical development" rewritten; earlier drafts are found at User:Phlsph7/Philosophy_-_history_section; for a detailed discussion, see Talk:Philosophy#Changes_to_the_section_"Historical_overview"; many of the replaced passages with sources were moved to the corresponding main articles |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

== Historical overview {{anchor|History}} == |

== Historical overview {{anchor|History}} == |

||

{{ |

{{main|History of philosophy}} |

||

The history of philosophy studies the development of philosophical thought. It aims to provide a systematic and chronological exposition of philosophical concepts and doctrines.{{sfn|Copleston|2003|p=4–6}}{{sfn|Santinello|Piaia|2010|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=gC2J3V7_TPUC&pg=PA487 487–488]}}{{sfn|Verene|2008|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=hkDX-dxMHpoC&pg=PA6 6–8]}} Some theorists see it as a part of [[intellectual history]], but it also investigates questions not covered by intellectual history such as whether the theories of past philosophers are true and philosophically relevant today.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Laerke|Smith|Schliesser|2013|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=RssWDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA115 115–118]}} |2={{harvnb|Verene|2008|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=hkDX-dxMHpoC&pg=PA6 6–8]}} |3={{harvnb|Frede|2022|p=x}} |4={{harvnb|Beaney|2013|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=eMZoAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA60 60]}} }}</ref> The history of philosophy is primarily concerned with theories based on [[Rationality|rational]] inquiry and argumentation. However, some historians understand it in a looser sense that includes [[myth]]s, [[Religion|religious teachings]], and proverbial lore.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Scharfstein|1998|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=iZQy2lu70bwC&pg=PA1 1–4]}} |2={{harvnb|Perrett|2016|loc=Is there Indian philosophy?}} |3={{harvnb|Smart|2008|pp=1–3}} |4={{harvnb|Rescher|2014|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=2yEvBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA173 173]}} |5={{harvnb|Parkinson|2005|p=1–2}} }}</ref> The main traditions in the history of philosophy include [[Western philosophy|Western]], [[Islamic philosophy|Arabic-Persian]], [[Indian philosophy|Indian]], and [[Chinese philosophy]], the latter two of which are often referred to under the broader heading of ''[[Eastern philosophy]]''. Other influential philosophical traditions are [[Japanese philosophy]], [[Latin American philosophy]], and [[African philosophy]].{{sfn|Smart|2008|pp=1–11}} |

|||

=== Western === |

|||

{{main|Western philosophy}} |

|||

[[File:Aristoteles_der_Stagirit.jpg|thumb|alt=Photo of a statue of Aristotle|Statue of [[Aristotle]] (384–322 BCE), a major figure of ancient Greek philosophy, in Aristotle's Park, [[Stageira Chalkidikis|Stagira]]]] |

|||

{{split section|History of philosophy|date=May 2023|discuss=Wikipedia_talk:WikiProject_Philosophy#Proper_article_for_"History_of_philosophy"}} |

|||

{{More citations needed|date=May 2022|1=section}} |

|||

Western philosophy covers philosophical thought linked to the geographical region and cultural heritage of the [[Western world]].{{sfn|Iannone|2013|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=AyB6GXM-CZkC&pg=PT12 12]}}{{sfn|Kelly|2004|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=AFwr3CCoqAEC&pg=PR11 Preface]}} It originated in [[Ancient Greece]] in the 6th century BCE with the [[Presocratics]]. They attempted to provide rational explanations of the [[cosmos]] as a whole.{{sfn|Blackson|2011|loc=[https://books.google.com/books?id=89zzlbsG1KgC&pg=PT13 Introduction]}}{{sfn|Graham|2023|loc=lead section, 1. Presocratic Thought}}{{sfn|Duignan|2010|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=MfBS-RXJ5RsC&pg=PA9 9–11]}} The philosophy following them was shaped by [[Socrates]], [[Plato]], and [[Aristotle]]. They expanded the range of topics to questions like [[Ethics|how people should act]], [[Epistemology|how to arrive at knowledge]], and what the [[Metaphysics|nature of reality]] and [[mind]] is.{{sfn|Graham|2023|loc=lead section, 2. Socrates, 3. Plato, 4. Aristotle}}{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=Socrates, Plato, Aristotle}} The later part of the ancient period was marked by the emergence of philosophical movements including like [[Epicureanism]], [[Stoicism]], [[Skepticism]], and [[Neoplatonism]].{{sfn|Long|1986|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=3s6DILqP1MwC&pg=PA1 1]}}{{sfn|Blackson|2011|loc=Chapter 10}}{{sfn|Graham|2023|loc=6. Post-Hellenistic Thought}} The medieval period started in the 5th century CE. Its focus was on religious topics and many thinkers used ancient philosophy to explain and further elaborate [[Christian doctrine]].<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Duignan|2010a|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=5HoJ77q1TN8C&pg=PA9 9]}} |2={{harvnb|Lagerlund|2020|p=v}} |3={{harvnb|Marenbon|2023|loc=lead section}} |4={{harvnb|MacDonald|Kretzmann|1996|loc=lead section}} }}</ref>{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=Part II: Medieval and Renaissance Philosophy}}{{sfn|Adamson|2019|pp=3–4}} |

|||

In one general sense, philosophy is associated with [[wisdom]], intellectual culture, and a search for knowledge. In this sense, all cultures and literate societies ask philosophical questions, such as "how are we to live" and "what is the nature of reality". A broad and impartial conception of philosophy, then, finds a reasoned inquiry into such matters as [[reality]], [[morality]], and life in all world civilizations.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy|date=2011-06-09|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|isbn=9780195328998|editor1-last=Garfield|editor1-first=Jay L|chapter=Introduction|doi=10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195328998.001.0001|editor2-last=Edelglass|editor2-first=William|chapter-url=https://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195328998.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195328998|access-date=19 December 2019|archive-date=31 March 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190331133725/http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195328998.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780195328998|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Renaissance]] period started in the 14th century and saw a renewed interest in various schools of Ancient philosophy, in particular [[Platonism]]. The idea of [[Renaissance humanism|humanism]] also emerged in this period.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Parkinson|2005|p=1–14}} |2={{harvnb|Adamson|2022|pp=155–157}} |3={{harvnb|Grayling|2019|loc=Philosophy in the Renaissance}} |4={{harvnb|Chambre|Maurer|Stroll|McLellan|2023|loc=Renaissance philosophy}} }}</ref> The following modern period started in the 17th century. One of its central concerns was how philosophical and [[Science|scientific]] knowledge are created. Specific importance was given to the [[Rationalism|role of reason]] and [[Empiricism|sensory experience]].{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=The Rise of Modern Thought; The Eighteenth-century Enlightenment}}{{sfn|Anstey|Vanzo|2023|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=2LytEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA236 236–237]}} Many of these innovations were used in the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment movement]] to challenge traditional authorities.{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=The Eighteenth-Century Enlightenment}}{{sfn|Kenny|2006|pp=90–92}} Various attempts to develop all-inclusive systems of philosophy were made in the later part of the modern period, for example, by [[German idealism]].{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=Philosophy in the Nineteenth Century}} Influential developments in 20th-century philosophy were the emergence and application of [[formal logic]] and the focus on the [[Linguistic turn|role of language]] as well as philosophical movements like [[Phenomenology (philosophy)|phenomenology]] and [[pragmatism]].{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=Philosophy in the Twentieth Century}}{{sfn|Zack|2009|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=lSgf2OuCpcoC&pg=PA255 255, 331–384]}} |

|||

=== Western philosophy<!--'History of Western philosophy' and 'History of western philosophy' redirect here--> === |

|||

{{Main|Western philosophy}} |

|||

[[File:Aristoteles_der_Stagirit.jpg|thumb|Statue of [[Aristotle]] (384–322 BCE), a major figure of ancient Greek philosophy, in Aristotle's Park, [[Stageira Chalkidikis|Stagira]]]] |

|||

[[Western philosophy]] is the philosophical tradition of the [[Western world]], dating back to [[Pre-Socratic philosophy|pre-Socratic]] thinkers who were active in 6th-century [[Ancient Greece|Greece]] (BCE), such as [[Thales]] ({{Circa|624|545|lk=yes}} BCE) and [[Pythagoras]] ({{Circa|570|495|lk=no}} BCE) who practiced a "love of wisdom" ({{Lang-la|philosophia}})<ref name=":02">{{Cite book|last1=Hegel|first1=Georg Wilhelm Friedrich|url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=b_VvghYDArwC}}|title=Lectures on the History of Philosophy: Greek philosophy|last2=Brown|first2=Robert F.|date=2006|publisher=Clarendon Press|isbn=978-0-19-927906-7|page=33}}</ref> and were also termed "students of nature" ({{Lang-la|physiologoi|label=none}}). |

|||

=== Arabic-Persian === |

|||

[[Western philosophy]] can be divided into three eras: |

|||

{{main|Islamic philosophy}} |

|||

Arabic-Persian philosophy is the philosophical tradition of [[Arabic]]- and [[Persian language|Persian]]-speaking regions.{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=Arabic-Persian Philosophy}}{{sfn|Adamson|2016|p=5}} It started in the early 9th century CE and had its peak period during the [[Islamic Golden Age]]. It was strongly influenced by Ancient Greek philosophers and employed their ideas to elaborate and interpret the teachings of the [[Quran]].<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Adamson|Taylor|2004|p=1}} |2={{harvnb|EB staff|2020}} |3={{harvnb|Grayling|2019|loc=Arabic-Persian Philosophy}} |4={{harvnb|Adamson|2016|p=5–6}} }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Avicenna_Portrait_on_Silver_Vase_-_Museum_at_BuAli_Sina_(Avicenna)_Mausoleum_-_Hamadan_-_Western_Iran_(7423560860).jpg|thumb|alt=Portrait of Avicenna on a Silver Vase|An Iranian portrait of [[Avicenna]] on a Silver Vase. He was one of the most influential philosophers of the [[Islamic Golden Age]].]] |

|||

# [[Ancient Greek philosophy|Ancient]] ([[Greco-Roman world|Greco-Roman]]). |

|||

# [[Medieval philosophy]] (referring to Christian European thought). |

|||

# [[Modern philosophy]] (beginning in the 17th century). |

|||

[[Al-Kindi]] is usually regarded as the first philosopher of this tradition. He translated and interpreted many works of Aristotle and Neoplatonists in his attempt to show that there is a harmony between [[reason]] and [[faith]].<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Esposito|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=6VeCWQfVNjkC&pg=PA246 246]}} |2={{harvnb|Nasr|Leaman|2013|loc=11. Al-Kindi}} |3={{harvnb|Nasr|2006|p=109–110}} |4={{harvnb|Adamson|2020|loc=lead section}} }}</ref> [[Avicenna]] also followed this goal and developed a comprehensive philosophical system to provide a rational understanding of reality encompassing science, religion, and mysticism.{{sfn|Gutas|2016}}{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=Ibn Sina (Avicenna)}} [[Al-Ghazali]] was a strong critic of the idea that reason can arrive at a true understanding of reality and God. He formulated a detailed [[The Incoherence of the Philosophers|critique of philosophy]] and tried to assign philosophy a more limited place beside the teachings of the Quran and mystical insight.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Adamson|2016|p=140–146}} |2={{harvnb|Dehsen|2013|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=cU7cAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA75 75]}} |3={{harvnb|Griffel|2020|loc=lead section, 3. Al-Ghazâlî’s “Refutations” of falsafa and Ismâ’îlism, 4. The Place of Falsafa in Islam}} }}</ref> Following Al-Ghazali and the end of the Islamic Golden Age, the influence of philosophical inquiry waned.{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=Ibn Rushd (Averroes)}}{{sfn|Kaminski|2017|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=KDUyDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA32 32]}} [[Mulla Sadra]] is often regarded as one of the most influential philosophers of the subsequent period.{{sfn|Rizvi|2021|loc=lead section, 3. Metaphysics, 4. Noetics — Epistemology and Psychology}}{{sfn|Chamankhah|2019|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=2GGtDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA73 73]}} |

|||

==== Ancient era ==== |

|||

While our knowledge of the ancient era begins with [[Thales]] in the 6th century BCE, little is known about the philosophers who came before [[Socrates]] (commonly known as [[Pre-Socratic philosophy|the pre-Socratics]]). The ancient era was dominated by [[Ancient Greek philosophy|Greek philosophical schools]]. Most notable among the schools influenced by Socrates' teachings were [[Plato]], who founded the [[Platonic Academy]], and his student [[Aristotle]], who founded the [[Peripatetic school]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Whitehead |first=Alfred North |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uJDEx6rPu1QC |title=Process and Reality |date=2010-05-11 |publisher=Simon & Schuster |isbn=978-1-4391-1836-8 |language=en|page=39}}</ref> Other ancient philosophical traditions influenced by Socrates included [[Cynicism (philosophy)|Cynicism]], [[Cyrenaics|Cyrenaicism]], [[Stoicism]], and [[Academic Skepticism]]. Two other traditions were influenced by Socrates' contemporary, [[Democritus]]: [[Pyrrhonism]] and [[Epicureanism]]. Important topics covered by the Greeks included [[metaphysics]] (with competing theories such as [[atomism]] and [[monism]]), [[cosmology]], the nature of the well-lived life (''[[eudaimonia]]''), the [[Epistemology|possibility of knowledge]], and the nature of reason ([[logos]]). With the rise of the [[Roman empire]], Greek philosophy was increasingly discussed in [[Latin]] by [[Ancient Rome|Romans]] such as [[Cicero]] and [[Seneca the Younger|Seneca]] (see [[Roman philosophy]]).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kenny |first=Anthony |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LwA44eCAUoIC |title=Ancient Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy |date=2004-06-17 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-162252-6 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

=== Indian === |

|||

{{main|Indian philosophy}} |

|||

[[Medieval philosophy]] (5th–16th centuries) took place during the period following the fall of the [[Western Roman Empire]] and was dominated by the rise of [[Christianity]]; it hence reflects [[Judeo-Christian]] theological concerns while also retaining a continuity with Greco-Roman thought. Problems such as the existence and nature of [[God]], the nature of [[faith]] and reason, metaphysics, and the [[problem of evil]] were discussed in this period. Some key medieval thinkers include [[Augustine of Hippo|Augustine]], [[Thomas Aquinas]], [[Boethius]], [[Anselm of Laon|Anselm]] and [[Roger Bacon]]. Philosophy for these thinkers was viewed as an aid to [[theology]] ({{Lang-la|ancilla theologiae|label=none}}), and hence they sought to align their philosophy with their interpretation of sacred scripture. This period saw the development of [[scholasticism]], a text critical method developed in [[medieval universities]] based on close reading and disputation on key texts. The [[Renaissance]] period saw increasing focus on classic Greco-Roman thought and on a robust [[humanism]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kenny |first=Anthony |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=p8Pab9HChqMC |title=Medieval Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy, Volume 2 |date=2007-05-31 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-162253-3 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

Indian philosophy covers philosophical thought that originated on the [[Indian subcontinent]].{{sfn|Gupta|2012|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=2mmpAgAAQBAJ&pg=PT8 8]}}{{sfn|Perrett|2016|loc=Indian philosophy: a brief historical overview}} One of its distinguishing features is its integrated exploration of the nature of reality, the ways of arriving at knowledge, and the [[Spirituality|spiritual]] question of how to reach [[Enlightenment (spiritual)|enlightenment]].{{sfn|Smart|2008|pp=3}}{{sfn|Grayling|2019|loc=Indian Philosophy}} It started around 900 BCE when the religious scriptures known as the [[Vedas]] were written. They contemplate issues concerning the relation between the [[Ātman (Hinduism)|self]] and [[Brahman|ultimate reality]] as well as the question of how [[Jiva|souls]] are reborn based on their [[Karma|past actions]].<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Perrett|2016|loc=Indian philosophy: a brief historical overview, The ancient period of Indian philosophy}} |2={{harvnb|Grayling|2019|loc=Indian Philosophy}} |3={{harvnb|Pooley|Rothenbuhler|2016|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=eY_2DQAAQBAJ&pg=PA1468 1468]}} |4={{harvnb|Andrea|Overfield|2015|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=x5-aBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA71 71]}} }}</ref> This period also saw the emergence of non-Vedic teachings, like [[Buddhism]] and [[Jainism]].{{sfn|Perrett|2016|loc=The ancient period of Indian philosophy}}{{sfn|Ruether|2004|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=MQFvAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA57 57]}} |

|||

==== Modern era ==== |

|||

[[File:Kant doerstling2.jpg|thumb|A painting of the influential modern philosopher [[Immanuel Kant]] (in the blue coat) with his friends. Other figures include [[Christian Jakob Kraus]], [[Johann Georg Hamann]], [[Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel the Elder|Theodor Gottlieb von Hippel]] and [[Karl Gottfried Hagen]].]] |

|||

[[Early modern philosophy]] in the Western world begins with thinkers such as [[Thomas Hobbes]] and [[René Descartes]] (1596–1650).<ref name="diane">{{cite book|author=Collinson, Diane|title=Fifty Major Philosophers, A Reference Guide|page=125}}</ref> Following the rise of natural science, [[modern philosophy]] was concerned with developing a secular and rational foundation for knowledge and moved away from traditional structures of authority such as religion, scholastic thought and the Church. Major modern philosophers include [[Spinoza]], [[Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz|Leibniz]], [[John Locke|Locke]], [[George Berkeley|Berkeley]], [[David Hume|Hume]], and [[Immanuel Kant|Kant]]. |

|||

The subsequent classical period started roughly 200 BCE and was characterized by the emergence of the six orthodox schools of Hinduism. They are known as the [[astika]]s and are [[Nyaya|Nyāyá]], [[Vaisheshika|Vaiśeṣika]], [[Samkhya|Sāṃkhya]], [[Yoga]], [[Mīmāṃsā]], and [[Vedanta|Vedanta]].{{sfn|Perrett|2016|loc=Indian philosophy: a brief historical overview, The classical period of Indian philosophy, The medieval period of Indian philosophy}}{{sfn|Glenney|Silva|2019|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=gH6JDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT77 77]}}{{sfn|Adamson|Ganeri|2020|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=NCbTDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA101 101–109]}} The school of [[Advaita Vedanta]] developed later in this period. It claimed that [[Monism|everything is one]] and that the impression of a universe consisting of many distinct entities is an [[Maya (religion)|illusion]].{{sfn|Perrett|2016|loc=The medieval period of Indian philosophy}}{{sfn|Dalal|2021|loc=lead section, 2. Metaphysics}}{{sfn|Menon|loc=lead section}} The modern period began roughly 1800 CE and was shaped by the encounter with Western thought.{{sfn|Perrett|2016|loc=Indian philosophy: a brief historical overview, The modern period of Indian philosophy}}{{sfn|EB staff|2023}} Various philosophers tried to formulate comprehensive systems to harmonize diverse philosophical and religious teachings. For example, [[Swami Vivekananda]] used the teachings of Advaita Vedanta to argue that all the different religions are valid paths toward the one divine.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Banhatti|1995|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=jK5862eV7_EC&pg=PA151 151–154]}} |2={{harvnb|Bilimoria|2018|pp=529–531}} |3={{harvnb|Rambachan|1994|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=b9EJBQG3zqUC&pg=PA91 91–92]}} }}</ref> |

|||

[[19th-century philosophy]] (sometimes called [[late modern philosophy]]) was influenced by the wider 18th-century movement termed "[[the Enlightenment]]", and includes figures such as [[Hegel]], a key figure in [[German idealism]]; [[Kierkegaard]], who developed the foundations for [[existentialism]]; [[Thomas Carlyle]], representative of the [[great man theory]]; [[Nietzsche]], a famed anti-Christian; [[John Stuart Mill]], who promoted [[utilitarianism]]; [[Karl Marx]], who developed the foundations for [[communism]]; and the American [[William James]]. The 20th century saw the split between [[analytic philosophy]] and [[continental philosophy]], as well as philosophical trends such as [[Phenomenology (philosophy)|phenomenology]], [[existentialism]], [[logical positivism]], [[pragmatism]] and the [[linguistic turn]] (see [[Contemporary philosophy]]).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kenny |first=Anthony |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qIkSDAAAQBAJ |title=The Rise of Modern Philosophy: A New History of Western Philosophy, Volume 3 |date=2006-06-29 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-875277-6 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Chinese === |

||

{{ |

{{main|Chinese philosophy}} |

||

[[File:Half Portraits of the Great Sage and Virtuous Men of Old - Confucius.jpg|thumb|alt=Painting of Confucius|Confucius (551–479 BCE) was one of the earliest and most influential Chinese philophers]] |

|||

==== Pre-Islamic philosophy ==== |

|||

The regions of the [[Fertile Crescent]], [[Iran]] and [[Arabia]] are home to the earliest known philosophical wisdom literature.{{Citation needed|date=March 2022}} |

|||

Chinese philosophy encompasses the philosophical and intellectual heritage of [[China]]. Compared to the other main traditions, it placed less emphasis on questions of ultimate reality. It was more interested in practical questions associated with right social conduct and government.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Smart|2008|pp=3, 70–71}} |2={{harvnb|EB staff|2017}} |3={{harvnb|Littlejohn|2023}} |4={{harvnb|Grayling|2019|loc=Chinese Philosophy}} |5={{harvnb|Mou|2009|pp=43–45}} }}</ref> It originated in the 6th century BCE when the schools of [[Confucianism]] and [[Daoism]] emerged. Confucian thought focused on different forms of moral [[virtue]]s and explored how they lead to harmony in society.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|EB staff|2017}} |2={{harvnb|Smart|2008|pp=70–76}} |3={{harvnb|Littlejohn|2023|loc=1b. Confucius (551-479 B.C.E.) of the Analects}} |4={{harvnb|Boyd|Timpe|2021|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=OIskEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA64 64–66]}} |5={{harvnb|Marshev|2021|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=DPQTEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA100 100–101]}} }}</ref> Daoism broadened this focus to also include questions about the relation between humans and nature.<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|EB staff|2017}} |2={{harvnb|Slingerland|2007|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=gSReaja3V3IC&pg=PA77 77–78]}} |3={{harvnb|Grayling|2019|loc=Chinese Philosophy}} }}</ref> The introduction of Buddhism to China in the following period resulted in the development of [[Chinese Buddhism|new forms of Buddhism]].{{sfn|Littlejohn|2023|loc=Early Buddhism in China}} |

|||

According to the [[Assyriology|assyriologist]] [[Marc Van de Mieroop]], [[Babylonia]]n philosophy was a highly developed system of thought with a unique approach to knowledge and a focus on writing, [[lexicography]], divination, and law.{{sfn|''Philosophy before the Greeks''|2015|pp=vii-viii, 187-188}} It was also a [[Multilingualism|bilingual]] intellectual culture, based on [[Sumerian language|Sumerian]] and [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]].{{sfn|''Philosophy before the Greeks''|2015|p=218}} |

|||

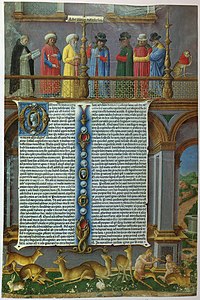

[[File:History_of_civilization,_being_a_course_of_lectures_on_the_origin_and_development_of_the_main_institutions_of_mankind_(1887)_(14577423529).jpg|thumb|A page of ''The Maxims of Ptahhotep,'' traditionally attributed to the [[Vizier (Ancient Egypt)|Vizier]] [[Ptahhotep]] ({{c.|2375|lk=no}}–2350 BCE)]] |

|||

Early [[Wisdom literature]] from the Fertile Crescent was a genre that sought to instruct people on ethical action, practical living, and virtue through stories and proverbs. In [[Ancient Egypt]], these texts were known as ''[[sebayt]]'' ('teachings'), and they are central to our understandings of [[Ancient Egyptian philosophy]]. The most well known of these texts is ''[[The Maxims of Ptahhotep]].''<ref>{{cite book|last=Lichtheim|first=Miriam|author-link=Miriam Lichtheim |year=1976|title=Ancient Egyptian Literature, Volume II: The New Kingdom|pages=61 ff|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=0-520-03615-8}}</ref> Theology and cosmology were central concerns in Egyptian thought. Perhaps the earliest form of a [[Monotheism|monotheistic]] [[theology]] also emerged in Egypt, with the rise of the [[Atenism|Amarna theology (or Atenism)]] of [[Akhenaten]] (14th century BCE), which held that the solar creation deity [[Aten]] was the only god. This has been described as a "monotheistic revolution" by [[Egyptology|egyptologist]] [[Jan Assmann]], though it also drew on previous developments in Egyptian thought, particularly the "New Solar Theology" based around [[Amun|Amun-Ra]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Najovits|first=Simson|year=2004|title=Egypt, the Trunk of the Tree, A Modern Survey of and Ancient Land, Vol. II|page=131|location=New York|publisher=Algora Publishing|isbn=978-0875862569}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{cite book|last=Assmann|first=Jan|year=2004|chapter-url=http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/2354/1/Assmann_Theological_responses_to_Amarna_2004.pdf|chapter=Theological Responses to Amarna|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200518232700/http://archiv.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/propylaeumdok/2354/1/Assmann_Theological_responses_to_Amarna_2004.pdf|archive-date=18 May 2020|url-status=live|editor-last1=Knoppers|editor-first1=Gary N.|editor-last2=Hirsch|editor-first2=Antoine|title=Egypt, Israel, and the Ancient Mediterranean World. Studies in Honor of Donald B. Redford|location=Leiden/Boston|pages=179–191}}</ref> These theological developments also influenced the post-Amarna [[New Kingdom of Egypt|Ramesside]] theology, which retained a focus on a single creative solar deity (though without outright rejection of other gods, which are now seen as manifestations of the main solar deity). This period also saw the development of the concept of the [[Ancient Egyptian conception of the soul|''ba'']] (soul) and its relation to god.<ref name=":4"/> |

|||

The modern period in Chinese philosophy began in the early 20th century and was shaped by the influence of and reactions to Western philosophy. Of particular importance were the ideas of [[Karl Marx]] on [[class struggle]], [[socialism]], and [[communism]]. They led to the development of [[Chinese Marxism]] and resulted in a significant transformation of the political landscape when [[Mao Zedong]] worked on their practical implementation in the form of a [[communist revolution]].<ref>{{multiref2 |1={{harvnb|Littlejohn|2023|loc=5. The Chinese and Western Encounter in Philosophy}} |2={{harvnb|Mou|2009|pp=473–480, 512–513}} |3={{harvnb|Qi|2014|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=nxWkAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA99 99–100]}} }}</ref> |

|||

[[Jewish philosophy]] and [[Christian philosophy]] are religious-philosophical traditions that developed both in the Middle East and in Europe, which both share certain early Judaic texts (mainly the [[Tanakh]]) and monotheistic beliefs. Jewish thinkers such as the [[Geonim]] of the [[Talmudic Academies in Babylonia]] and [[Maimonides]] engaged with Greek and Islamic philosophy. Later Jewish philosophy came under strong Western intellectual influences and includes the works of [[Moses Mendelssohn]] who ushered in the [[Haskalah]] (the Jewish Enlightenment), [[Jewish existentialism]], and [[Reform Judaism]].<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Frank |first1=Daniel |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2e_O1CbFwA8C |title=History of Jewish Philosophy |last2=Leaman |first2=Oliver |date=2005-10-20 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-134-89435-2 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Bartholomew |first1=Craig G. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4xe-AgAAQBAJ |title=Christian Philosophy: A Systematic and Narrative Introduction |last2=Goheen |first2=Michael W. |date=2013-10-15 |publisher=Baker Academic |isbn=978-1-4412-4471-0 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The various traditions of [[Gnosticism]], which were influenced by both Greek and Abrahamic currents, originated around the first century and emphasized spiritual knowledge (''[[gnosis]]'').<ref>{{Cite book |last=Churton |first=Tobias |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qlwoDwAAQBAJ |title=Gnostic Philosophy: From Ancient Persia to Modern Times |date=2005-01-25 |publisher=Simon & Schuster |isbn=978-1-59477-767-7 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

Pre-Islamic [[Iranian philosophy]] begins with the work of [[Zoroaster]], one of the first promoters of [[monotheism]] and of the [[Dualistic cosmology|dualism]] between good and evil.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Nasr |first1=S. H. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Bu3WAAAAMAAJ |title=An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, Vol. 2: Ismaili Thought in the Classical Age |last2=Aminrazavi |first2=Mehdi |last3=Jozi |first3=M. R. |date=2008-09-30 |publisher=Bloomsbury Academic |isbn=978-1-84511-542-5 |language=en}}</ref> This dualistic cosmogony influenced later Iranian developments such as [[Manichaeism]], [[Mazdakism]], and [[Zurvanism]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Keddie |first=Nikki R. |author-link=Nikki Keddie |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5vnIBQAAQBAJ |title=Iran: Religion, Politics and Society: Collected Essays |date=2013-10-28 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-136-28041-2 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=de Blois |first=François |date=2000 |title=Dualism in Iranian and Christian Traditions |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25187928 |journal=Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=1–19 |doi=10.1017/S1356186300011913 |jstor=25187928 |s2cid=162835432 |issn=1356-1863}}</ref> |

|||

==== Islamic philosophy ==== |

|||

{{See also|Islamic philosophy|}}[[File:Avicenna_Portrait_on_Silver_Vase_-_Museum_at_BuAli_Sina_(Avicenna)_Mausoleum_-_Hamadan_-_Western_Iran_(7423560860).jpg|right|thumb|An Iranian portrait of [[Avicenna]] on a Silver Vase. He was one of the most influential philosophers of the [[Islamic Golden Age]].]] |

|||

[[Islamic philosophy]] is the philosophical work originating in the [[Islamic culture|Islamic tradition]] and is mostly done in [[Arabic]]. It draws from the religion of Islam as well as from Greco-Roman philosophy. After the [[Early Muslim conquests|Muslim conquests]], the [[Graeco-Arabic translation movement|translation movement]] (mid-eighth to the late tenth century) resulted in the works of Greek philosophy becoming available in Arabic.<ref>{{cite book|last=Gutas|first=Dimitri|year=1998|title=Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th centuries)|publisher=Routledge|pages=1–26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Early Islamic philosophy]] developed the Greek philosophical traditions in new innovative directions. This intellectual work inaugurated what is known as the [[Islamic Golden Age]]. The two main currents of early Islamic thought are [[Kalam]], which focuses on [[Islamic theology]], and [[Falsafa]], which was based on [[Aristotelianism]] and [[Neoplatonism]]. The work of Aristotle was very influential among philosophers such as [[Al-Kindi]] (9th century), [[Avicenna]] (980 – June 1037), and [[Averroes]] (12th century). Others such as [[Al-Ghazali]] were highly critical of the methods of the Islamic Aristotelians and saw their metaphysical ideas as heretical. Islamic thinkers like [[Ibn al-Haytham]] and [[Al-Biruni]] also developed a [[scientific method]], experimental medicine, a theory of optics, and a legal philosophy. [[Ibn Khaldun]] was an influential thinker in [[philosophy of history]]. |

|||

Islamic thought also deeply influenced European intellectual developments, especially through the commentaries of Averroes on Aristotle. The [[Mongol invasions of the Levant|Mongol invasions]] and the [[Siege of Baghdad (1258)|destruction of Baghdad]] in 1258 are often seen as marking the end of the Golden Age.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Cooper|first1=William W.|last2=Yue|first2=Piyu|year=2008|title=Challenges of the Muslim world: present, future and past|publisher=Emerald Group Publishing|isbn=978-0-444-53243-5}}</ref> Several schools of Islamic philosophy continued to flourish after the Golden Age, however, and include currents such as [[Illuminationist philosophy]], [[Sufi philosophy]], and [[Transcendent theosophy]]. |

|||

The 19th- and 20th-century [[Arab world]] saw the ''[[Nahda]]'' movement (literally meaning 'The Awakening'; also known as the 'Arab Renaissance'), which had a considerable influence on [[contemporary Islamic philosophy]]. |

|||

=== Eastern philosophy === |

|||

{{Main|Eastern philosophy||}} |

|||

==== Indian philosophy ==== |

|||

{{Main|Indian philosophy||}} |

|||

[[File:Raja_Ravi_Varma_-_Sankaracharya.jpg|thumb|[[Adi Shankara]] is one of the most frequently studied [[Hindu]] philosophers.<ref>{{cite book|author=N.V. Isaeva|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hshaWu0m1D4C|title=Shankara and Indian Philosophy|publisher=State University of New York Press|year=1992|isbn=978-0-7914-1281-7|pages=1–5|oclc=24953669|access-date=11 November 2018|archive-date=14 January 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200114040317/https://books.google.com/books?id=hshaWu0m1D4C|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=John Koller|chapter-url=https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781136696862/chapters/10.4324%2F9780203813010-17|title=Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion|publisher=Routledge|year=2013|isbn=978-1-136-69685-5|editor=Chad Meister and Paul Copan|doi=10.4324/9780203813010|chapter=Shankara|access-date=13 November 2018|archive-date=12 November 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181112223414/https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/e/9781136696862/chapters/10.4324%2F9780203813010-17|url-status=live}}</ref>]] |

|||

[[Indian philosophy]] ({{lang-sa|{{IAST|darśana}}|lit=point of view', 'perspective}})<ref>{{cite book|last=Johnson|first=W. J.|year=2009|chapter-url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095700856|chapter=darśana|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210309015018/https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095700856|archive-date=9 March 2021|url-status=live|title=Oxford Reference}} From: {{cite book|chapter-url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198610250.001.0001/acref-9780198610250-e-710|chapter=darśan(a)|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200903141043/https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780198610250.001.0001/acref-9780198610250-e-710|archive-date=3 September 2020|url-status=live|title=A Dictionary of Hinduism|year=2009 |editor-last=Johnson|editor-first=W. J.|location=Oxford|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|isbn=9780191726705|doi=10.1093/acref/9780198610250.001.0001}}</ref> refers to the diverse philosophical traditions that emerged since the ancient times on the [[Indian subcontinent]]. Indian philosophy chiefly considers epistemology, theories of consciousness and theories of mind, and the physical properties of reality.<ref>{{cite book | chapter-url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/epistemology-india/ | title=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy | chapter=Epistemology in Classical Indian Philosophy | year=2021 | publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University }}</ref> <ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00343 | doi-access=free | title=How do Theories of Cognition and Consciousness in Ancient Indian Thought Systems Relate to Current Western Theorizing and Research? | year=2016 | last1=Sedlmeier | first1=Peter | last2=Srinivas | first2=Kunchapudi | journal=Frontiers in Psychology | volume=7 | page=343 | pmid=27014150 | pmc=4791389 }}</ref> <ref>{{cite web | url=https://science.thewire.in/society/history/erwin-schrodinger-quantum-mechanics-philosophy-of-physics-upanishads/ | title=What Erwin Schrödinger Said About the Upanishads – the Wire Science }}</ref> Indian philosophical traditions share various key concepts and ideas, which are defined in different ways and accepted or rejected by the different traditions. These include concepts such as [[Dharma|''dhárma'']], ''[[karma]]'', ''[[Pramana|pramāṇa]],'' ''[[duḥkha]], [[saṃsāra]]'' and ''[[Moksha|mokṣa]].<ref>{{cite book|author=Young|first=William A.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GRoqAQAAMAAJ|title=The World's Religions: Worldviews and Contemporary Issues|publisher=Pearson Prentice Hall|year=2005|isbn=978-0-13-183010-3|pages=61–64, 78–79|access-date=10 November 2018|archive-date=17 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191217032152/https://books.google.com/books?id=GRoqAQAAMAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Mittal|first1=Sushil|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XpxADwAAQBAJ|title=Religions of India: An Introduction|last2=Thursby|first2=Gene|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2017|isbn=978-1-134-79193-4|pages=3–5, 15–18, 53–55, 63–67, 85–88, 93–98, 107–15|access-date=11 November 2018|archive-date=17 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191217032143/https://books.google.com/books?id=XpxADwAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref>'' |

|||

Some of the earliest surviving Indian philosophical texts are the [[Upanishads]] of the [[Vedic period#Later Vedic period (c. 1000 – c. 600 BCE)|later Vedic period]] (1000–500 BCE), which are considered to preserve the ideas of [[Historical Vedic religion|Brahmanism]]. Indian philosophical traditions are commonly grouped according to their relationship to the Vedas and the ideas contained in them. [[Jainism]] and [[Buddhism]] originated at the end of the [[Vedic period]], while the various traditions grouped under [[Hinduism]] mostly emerged after the Vedic period as independent traditions. Hindus generally classify Indian philosophical traditions as either orthodox ([[Āstika and nāstika|''āstika'']]) or heterodox (''nāstika'') depending on whether they accept the authority of the [[Vedas]] and the theories of ''[[brahman]]'' and [[Ātman (Hinduism)|''ātman'']] found therein.<ref>{{cite book|first=John |last=Bowker|title=The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions|url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=5fSQQgAACAAJ}}|year=1999|publisher=Oxford University Press, Incorporated|isbn=978-0-19-866242-6|page=259}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Doniger, Wendy|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=c8vRAgAAQBAJ|title=On Hinduism|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2014|isbn=978-0-19-936008-6|page=46|author-link=Wendy Doniger|access-date=25 December 2016|archive-date=30 January 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170130223555/https://books.google.com/books?id=c8vRAgAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The schools which align themselves with the thought of the Upanishads, the so-called "orthodox" or "[[Hinduism|Hindu]]" traditions, are often classified into six ''[[Hindu philosophy|darśanas]]'' or philosophies:[[Samkhya|Sānkhya]], [[Yoga (philosophy)|Yoga]], [[Nyaya|Nyāya]], [[Vaisheshika]], [[Mīmāṃsā|Mimāmsā]] and [[Vedanta|Vedānta]].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Kesarcodi-Watson|first=Ian|year=1978|title=Hindu Metaphysics and Its Philosophies: Śruti and Darsána|journal=International Philosophical Quarterly|volume=18|issue=4|pages=413–432|doi=10.5840/ipq197818440}}</ref> |

|||

The doctrines of the Vedas and Upanishads were interpreted differently by these six schools of [[Hindu philosophy]], with varying degrees of overlap. They represent a "collection of philosophical views that share a textual connection", according to Chadha (2015).<ref>{{cite book|last=Chadha|first=M.|year=2015|title=The Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Philosophy of Religion|editor-last=Oppy|editor-first=G.|editor-link=Graham Oppy|location=London|publisher=[[Routledge]]|isbn=978-1844658312|pages=127–28}}</ref> They also reflect a tolerance for a diversity of philosophical interpretations within Hinduism while sharing the same foundation.<ref name="Sharma1990p1" group="lower-roman">{{cite book|author=Sharma|first=Arvind|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jKewCwAAQBAJ|title=A Hindu Perspective on the Philosophy of Religion|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|year=1990|isbn=978-1-349-20797-8|access-date=11 November 2018|archive-date=12 January 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200112222617/https://books.google.com/books?id=jKewCwAAQBAJ|url-status=live|quote=The attitude towards the existence of God varies within the Hindu religious tradition. This may not be entirely unexpected given the tolerance for doctrinal diversity for which the tradition is known. Thus of the six orthodox systems of Hindu philosophy, only three address the question in some detail. These are the schools of thought known as Nyaya, Yoga and the theistic forms of Vedanta.|pages=1–2}}</ref> |

|||

Hindu philosophers of the six orthodox schools developed systems of epistemology (''[[pramana]]'') and investigated topics such as metaphysics, ethics, psychology (''[[guṇa]]''), [[hermeneutics]], and [[soteriology]] within the framework of the Vedic knowledge, while presenting a diverse collection of interpretations.<ref name="frazierintrop2">{{cite book|last1=Frazier|first1=Jessica|author-link=Jessica Frazier|url=https://archive.org/details/continuumcompani00fraz|title=The Continuum companion to Hindu studies|date=2011|publisher=Continuum|isbn=978-0-8264-9966-0|location=London|pages=[https://archive.org/details/continuumcompani00fraz/page/n15 1]–15|url-access=limited}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Olson|first=Carl|year=2007|title=The Many Colors of Hinduism: A Thematic-historical Introduction|publisher=[[Rutgers University Press]]|isbn=978-0813540689|pages=101–19}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Deutsch|first=Eliot S.|author-link=Eliot Deutsch|year=2000|chapter=Karma as a 'Convenient Fiction' in the Advaita Vedānta|pages=245–48|title=Philosophy of Religion: Indian Philosophy|volume=4|editor-last=Perrett|editor-first=R.|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-0815336112}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Grimes|first=John A.|title=A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English|date=January 1996 |location=Albany|publisher=[[State University of New York Press]]|isbn=978-0791430675|page=238}}</ref> The commonly named six orthodox schools were the competing philosophical traditions of what has been called the "Hindu synthesis" of [[History of Hinduism|classical Hinduism]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Hiltebeitel|first=Alf|author-link=Alf Hiltebeitel|year=2007|chapter=Hinduism|title=The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture|editor-last=Kitagawa|editor-first=J.|editor-link=Joseph Kitagawa|location=London|publisher=Routledge}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Minor|first=Robert|year=1986|title=Modern Indian Interpreters of the Bhagavad Gita|location=Albany|publisher=[[State University of New York Press]]|isbn=0-88706-297-0|pages=74–75, 81}}</ref> |

|||

<ref>{{cite web|last=Doniger|first=Wendy|year=2018|orig-year=1998|title=Bhagavad Gita|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bhagavadgita|website=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]|access-date=10 November 2018|archive-date=21 August 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180821140609/https://www.britannica.com/topic/Bhagavadgita|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

There are also other schools of thought which are often seen as "Hindu", though not necessarily orthodox (since they may accept different scriptures as normative, such as the [[Tantras (Hinduism)|Shaiva Agamas and Tantras]]), these include different schools of [[Shaivism|Shavism]] such as [[Pashupata Shaivism|Pashupata]], [[Shaiva Siddhanta]], [[Kashmir Shaivism|non-dual tantric Shavism]] (i.e. Trika, Kaula, etc.).<ref>Cowell and Gough (1882, Translators), ''The Sarva-Darsana-Samgraha or Review of the Different Systems of Hindu Philosophy by Madhva Acharya'', Trubner's Oriental Series.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Medieval Jain temple Anekantavada doctrine artwork.jpg|thumb|The parable of the blind men and the elephant illustrates the important Jain doctrine of [[Anekantavada|anēkāntavāda]].]] |

|||

The "Hindu" and "Orthodox" traditions are often contrasted with the "unorthodox" traditions (''nāstika,'' literally "those who reject"), though this is a label that is not used by the "unorthodox" schools themselves. These traditions reject the Vedas as authoritative and often reject major concepts and ideas that are widely accepted by the orthodox schools (such as ''Ātman'', ''Brahman'', and [[Ishvara|''Īśvara'']]).<ref name="bilimoriaastika">{{cite book|last=Bilimoria|first=Puruṣottama|year=2000|chapter=Hindu Doubts About God: Towards a Mīmāṃsā Deconstruction|title=Indian Philosophy|editor-last=Perrett|editor-first=Roy W.|location=London|publisher=[[Routledge]]|isbn=978-1135703226|page=88}}</ref> These unorthodox schools include Jainism (accepts ''ātman'' but rejects ''Īśvara,'' Vedas and ''Brahman''), Buddhism (rejects all orthodox concepts except rebirth and karma), [[Charvaka|Cārvāka]] (materialists who reject even rebirth and karma) and [[Ājīvika]] (known for their doctrine of fate).<ref name="bilimoriaastika"/><ref name="bhattacarv">{{cite book|last=Bhattacharya|first=R|year=2011|title=Studies on the Carvaka/Lokayata|publisher=Anthem|isbn=978-0857284334|pages=53, 94, 141–142}}</ref><ref name="bronkhorst">{{cite journal|last=Bronkhorst|first=Johannes|author-link=Johannes Bronkhorst|year=2012|title=Free will and Indian philosophy|journal=Antiquorum Philosophia |location=Roma Italy|volume=6|pages=19–30}}</ref><<ref>{{cite book|last=Lochtefeld|first=James|chapter=Ajivika|title=The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M|year=2002 |publisher=Rosen Publishing.|isbn=978-0823931798|page=22}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Basham|first=A. L.|year=2009|title=History and Doctrines of the Ajivikas – a Vanished Indian Religion, Motilal Banarsidass|isbn=978-8120812048|at=Chapter 1}}</ref><ref group="lower-roman">{{cite journal|last=Wynne|first=Alexander|year=2011|title=The ātman and its negation|journal=Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies|volume=33|number=1–2|pages=103–05|quote=The denial that a human being possesses a 'self' or 'soul' is probably the most famous Buddhist teaching. It is certainly its most distinct, as has been pointed out by [[Gunapala Piyasena Malalasekera|G.P. Malalasekera]]: 'In its denial of any real permanent Soul or Self, Buddhism stands alone.' A similar modern Sinhalese perspective has been expressed by [[Walpola Rahula Thero|Walpola Rahula]]: 'Buddhism stands unique in the history of human thought in denying the existence of such a Soul, Self or Ātman.' The 'no Self' or 'no soul' doctrine ({{Lang-sa|anātman}}; {{Lang-pi|anattan}}) is particularly notable for its widespread acceptance and historical endurance. It was a standard belief of virtually all the ancient schools of Indian Buddhism (the notable exception being the Pudgalavādins), and has persisted without change into the modern era.… [B]oth views are mirrored by the modern Theravādin perspective of [[Mahasi Sayadaw]] that 'there is no person or soul' and the modern Mahāyāna view of the fourteenth Dalai Lama that '[t]he Buddha taught that…our belief in an independent self is the root cause of all suffering.<span style="padding-right:.15em;">'</span>}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Jayatilleke|first=K. N.|author-link=K. N. Jayatilleke|year=2010|title=Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge|isbn=978-8120806191|pages=246–49, note 385 onwards}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Dundas|first=Paul|author-link=Paul Dundas|year=2002|title=The Jains|edition=2nd|location=London|publisher=[[Routledge]]|isbn=978-0415266055|pages=1–19, 40–44}}</ref> |

|||

[[Jain philosophy]] is one of the only two surviving "unorthodox" traditions (along with Buddhism). It generally accepts the concept of a permanent soul (''[[jiva]]'') as one of the five ''[[Āstika and nāstika|astikayas]]'' (eternal, infinite categories that make up the substance of existence). The other four being [[Dharma|''dhárma'']], ''[[adharma]]'', ''[[Akasha|ākāśa]]'' ('space'), and ''[[pudgala]]'' ('matter'). Jain thought holds that all existence is cyclic, eternal and uncreated.<ref>{{cite book|author=Hemacandra|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=quNpKVqABGMC|title=The Lives of the Jain Elders|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=1998|isbn=978-0-19-283227-6|pages=258–60|access-date=19 November 2018|archive-date=23 December 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161223030943/https://books.google.com/books?id=quNpKVqABGMC|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Tiwari|first=Kedar Nath|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Jb0rCQD9NcoC|title=Comparative Religion|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass|year=1983|isbn=978-81-208-0293-3|pages=78–83|access-date=19 November 2018|archive-date=24 December 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161224020536/https://books.google.com/books?id=Jb0rCQD9NcoC&printsec=frontcover|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Some of the most important elements of Jain philosophy are the [[Karma in Jainism|Jain theory of karma]], the doctrine of nonviolence ([[Ahimsa in Jainism|ahiṃsā]]) and the theory of "many-sidedness" or [[Anekantavada|Anēkāntavāda]]. The ''[[Tattvartha Sutra]]'' is the earliest known, most comprehensive and authoritative compilation of Jain philosophy.<ref>{{cite book|last=Jaini|first=Padmanabh S.|title=The Jaina Path of Purification|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wE6v6ahxHi8C|pages=81–83|year=1998|orig-year=1979|publisher=[[Motilal Banarsidass]]|isbn=81-208-1578-5|author-link=Padmanabh Jaini|access-date=19 November 2018|archive-date=16 February 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200216120741/https://books.google.com/books?id=wE6v6ahxHi8C|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Umāsvāti|author-link=Umāsvāti|year=1994|orig-year={{Circa|2nd}} – 5th century|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Rw4RwN9Q1kC|title=That Which Is: Tattvartha Sutra|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200806142119/https://books.google.ca/books?id=0Rw4RwN9Q1kC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb|archive-date=6 August 2020|translator-last=Tatia|translator-first=N.|publisher=[[HarperCollins]]|isbn=978-0-06-068985-8|pages=xvii–xviii}}</ref> |

|||

==== Buddhist philosophy ==== |

|||

{{Main|Buddhist philosophy}} |

|||

[[File:Monks_debating_at_Sera_monastery,_2013.webm|thumb|Monks debating at [[Sera monastery]], Tibet, 2013. According to Jan Westerhoff, "public debates constituted the most important and most visible forms of philosophical exchange" in ancient Indian intellectual life.{{sfn|Westerhoff|2018|p=13}}]] |

|||

Buddhist philosophy begins with the thought of [[Gautama Buddha]] ([[Floruit|fl.]] between 6th and 4th century BCE) and is preserved in the [[early Buddhist texts]]. It originated in the Indian region of [[Magadha]] and later spread to the rest of the [[Indian subcontinent]], [[East Asia]], [[Tibet]], [[Central Asia]], and [[Southeast Asia]]. In these regions, Buddhist thought developed into different philosophical traditions which used various languages (like [[Classical Tibetan|Tibetan]], [[Classical Chinese|Chinese]] and [[Pali]]). As such, Buddhist philosophy is a [[Transculturalism|trans-cultural]] and international phenomenon. |

|||

The dominant Buddhist philosophical traditions in [[East Asian Buddhism|East Asian]] nations are mainly based on Indian [[Mahayana]] Buddhism. The [[Theravāda Abhidhamma|philosophy of the Theravada]] school is dominant in [[Southeast Asia]]n countries like [[Sri Lanka]], [[Burma]] and [[Thailand]]. |

|||

Because [[Avidyā (Buddhism)|ignorance]] to the true nature of things is considered one of the roots of suffering (''[[dukkha]]''), Buddhist philosophy is concerned with epistemology, metaphysics, ethics and psychology. Buddhist philosophical texts must also be understood within the context of [[Buddhist meditation|meditative practices]] which are supposed to bring about certain cognitive shifts.{{sfn|Westerhoff|2018|p=8}} Key innovative concepts include the [[Four Noble Truths]] as an analysis of ''dukkha'', [[Impermanence|''anicca'']] (impermanence), and ''[[anatta]]'' (non-self).<ref group="lower-roman">{{cite book|author=Gombrich, Richard|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jZyJAgAAQBAJ|title=Theravada Buddhism|publisher=Routledge|year=2006|isbn=978-1-134-90352-8|access-date=10 November 2018|archive-date=16 August 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190816142222/https://books.google.com/books?id=jZyJAgAAQBAJ|url-status=live|quote=All phenomenal existence [in Buddhism] is said to have three interlocking characteristics: impermanence, suffering and lack of soul or essence.|page=47}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Buswell|first1=Robert E. Jr.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DXN2AAAAQBAJ|title=The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism|last2=Lopez|first2=Donald S. Jr.|publisher=Princeton University Press|year=2013|isbn=978-1-4008-4805-8|pages=42–47|access-date=10 November 2018|archive-date=17 May 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200517114246/https://books.google.com/books?id=DXN2AAAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

After the death of the Buddha, various groups began to systematize his main teachings, eventually developing comprehensive philosophical systems termed ''[[Abhidharma]]''.{{sfn|Westerhoff|2018|p=37}} Following the Abhidharma schools, Indian [[Mahayana]] philosophers such as [[Nagarjuna]] and [[Vasubandhu]] developed the theories of ''[[śūnyatā]]'' ('emptiness of all phenomena') and [[Yogachara#Vijñapti-mātra|''vijñapti-matra'']] ('appearance only'), a form of phenomenology or [[transcendental idealism]]. The [[Dignāga]] school of ''[[Pramana|pramāṇa]]'' ('means of knowledge') promoted a sophisticated form of [[Buddhist logico-epistemology|Buddhist epistemology]]. |

|||

There were numerous schools, sub-schools, and traditions of Buddhist philosophy in ancient and medieval India. According to Oxford professor of Buddhist philosophy [[Jan Westerhoff]], the major Indian schools from 300 BCE to 1000 CE were:{{sfn|Westerhoff|2018|p=xxiv}} the [[Mahāsāṃghika]] tradition (now extinct), the [[Sthavira nikāya|Sthavira]] schools (such as [[Sarvastivada|Sarvāstivāda]], [[Vibhajyavāda]] and [[Pudgalavada|Pudgalavāda]]) and the [[Mahayana]] schools. Many of these traditions were also studied in other regions, like Central Asia and China, having been brought there by Buddhist missionaries. |

|||

After the disappearance of Buddhism from India, some of these philosophical traditions continued to develop in the [[Tibetan Buddhist]], [[East Asian Buddhist]] and [[Theravada Buddhist]] traditions.<ref>{{cite book|last=Dreyfus|first=Georges B. J.|year=1997|title=Recognizing Reality: Dharmakirti's Philosophy and Its Tibetan Interpretations (Suny Series in Buddhist Studies)|page=22}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=JeeLoo Liu|title=Tian-tai Metaphysics vs. Hua-yan Metaphysics A Comparative Study}}</ref> |

|||

==== East Asian philosophy ==== |

|||

{{Main|Chinese philosophy|Korean philosophy|Japanese philosophy|Vietnamese philosophy|Eastern philosophy}} |

|||

[[File:'The Three Vinegar Tasters' by Kano Isen'in, c. 1802-1816, Honolulu Museum of Art, 6156.1.JPG|thumb|upright=1.35|[[Vinegar tasters|The Vinegar Tasters]] (Japan, [[Edo period]], 1802–1816) by Kanō Isen'in, depicting three prominent philosophical figures in [[Eastern philosophy|East Asian thought]]: [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]], [[Confucius]] and [[Laozi]]]] |

|||

[[File:延宾馆.JPG|right|thumb|Statue of the Neo-Confucian scholar [[Zhu Xi]] at the [[White Deer Grotto Academy]] in [[Mount Lu|Lushan Mountain]]]] |

|||

East Asian philosophical thought began in [[History of China#Ancient China|Ancient China]], and [[Chinese philosophy]] begins during the [[Western Zhou]] Dynasty and the following periods after its fall when the "[[Hundred Schools of Thought]]" flourished (6th century to 221 BCE).<ref>{{cite book|editor-last1=Garfield|editor-first1=Jay L.|editor-last2=Edelglass|editor-first2=William|year=2011|chapter=Chinese Philosophy|title=The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy|location=Oxford|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|isbn=9780195328998}}</ref><ref name="pe">{{cite book|last=Ebrey|first=Patricia|author-link=Patricia Buckley Ebrey|title=The Cambridge Illustrated History of China|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2010|location=New York|page=42}}</ref> This period was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments and saw the rise of the major philosophical schools of China such as [[Confucianism]] (also known as Ruism), [[Legalism (Chinese philosophy)|Legalism]], and [[Daoism|Taoism]] as well as numerous other less influential schools like [[Mohism]] and [[School of Naturalists|Naturalism]]. These philosophical traditions developed metaphysical, political and ethical theories such [[Tao]], [[Yin and yang]], [[Ren (Confucianism)|Ren]] and [[Li (Confucianism)|Li]]. |

|||

These schools of thought further developed during the [[Han dynasty|Han]] (206 BCE – 220 CE) and [[Tang dynasty|Tang]] (618–907 CE) eras, forming new philosophical movements like ''[[Xuanxue]]'' (also called ''Neo-Taoism''), and [[Neo-Confucianism]]. Neo-Confucianism was a syncretic philosophy, which incorporated the ideas of different Chinese philosophical traditions, including Buddhism and Taoism. Neo-Confucianism came to dominate the education system during the [[Song dynasty]] (960–1297), and its ideas served as the philosophical basis of the [[imperial exams]] for the [[Scholar-officials|scholar official class]]. Some of the most important Neo-Confucian thinkers are the Tang scholars [[Han Yu]] and [[Li Ao (philosopher)|Li Ao]] as well as the Song thinkers [[Zhou Dunyi]] (1017–1073) and [[Zhu Xi]] (1130–1200). Zhu Xi compiled the Confucian canon, which consists of the [[Four Books]] (the ''[[Great Learning]]'', the ''[[Doctrine of the Mean]]'', the ''[[Analects]]'' of Confucius, and the ''[[Mencius (book)|Mencius]]''). The Ming scholar [[Wang Yangming]] (1472–1529) is a later but important philosopher of this tradition as well. |

|||

Buddhism began arriving in China during the Han Dynasty, through a [[Silk Road transmission of Buddhism|gradual Silk road transmission]],<ref>{{cite news |first=Barbara |last=O'Brien |title=How Buddhism Came to China: A History of the First Thousand Years |url=https://www.learnreligions.com/buddhism-in-china-the-first-thousand-years-450147 |access-date=21 January 2021 |work=Learn Religions |date=June 25, 2019 |language=en |archive-date=27 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210127042320/https://www.learnreligions.com/buddhism-in-china-the-first-thousand-years-450147 |url-status=live }}</ref> and through native influences developed distinct Chinese forms (such as Chan/[[Zen]]) which spread throughout the [[East Asian cultural sphere]]. |

|||

Chinese culture was highly influential on the traditions of other East Asian states, and its philosophy directly influenced [[Korean philosophy]], [[Vietnamese philosophy]] and [[Japanese philosophy]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Chinese Religions and Philosophies |url=https://asiasociety.org/chinese-religions-and-philosophies |website=Asia Society |access-date=21 January 2021 |language=en |archive-date=16 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210116092034/https://asiasociety.org/chinese-religions-and-philosophies |url-status=live }}</ref> During later Chinese dynasties like the [[Ming Dynasty]] (1368–1644), as well as in the Korean [[Joseon dynasty]] (1392–1897), a resurgent [[Neo-Confucianism]] led by thinkers such as [[Wang Yangming]] (1472–1529) became the dominant school of thought and was promoted by the imperial state. In Japan, the [[Tokugawa shogunate]] (1603–1867) was also strongly influenced by Confucian philosophy.<ref>{{cite book|last=Perez|first=Louis G.|year=1998|title=The History of Japan|pages=57–59|location=Westport, CT|publisher=Greenwood Press|isbn=978-0-313-30296-1}}</ref> Confucianism continues to influence the ideas and worldview of the nations of the [[East Asian cultural sphere|Chinese cultural sphere]] today. |

|||

In the Modern era, Chinese thinkers incorporated ideas from Western philosophy. [[Chinese Marxist philosophy]] developed under the influence of [[Mao Zedong]], while a Chinese pragmatism developed under [[Hu Shih]]. The old traditional philosophies also began to reassert themselves in the 20th century. For example, [[New Confucianism]], led by figures such as [[Xiong Shili]], has become quite influential. Likewise, [[Humanistic Buddhism]] is a recent modernist Buddhist movement. |

|||

Modern Japanese thought meanwhile developed under strong Western influences such as the study of Western Sciences ([[Rangaku]]) and the modernist [[Meirokusha]] intellectual society, which drew from European enlightenment thought and promoted liberal reforms as well as Western philosophies like Liberalism and Utilitarianism. Another trend in modern Japanese philosophy was the "National Studies" ({{Lang|ja-latn|[[Kokugaku]]}}) tradition. This intellectual trend sought to study and promote ancient Japanese thought and culture. {{Lang|ja-latn|Kokugaku|italic=no}} thinkers such as [[Motoori Norinaga]] sought to return to a pure Japanese tradition which they called [[Shinto]] that they saw as untainted by foreign elements. |

|||

During the 20th century, the [[Kyoto School]], an influential and unique Japanese philosophical school, developed from Western [[Phenomenology (philosophy)|phenomenology]] and Medieval Japanese Buddhist philosophy such as that of [[Dogen]]. |

|||

=== African philosophy === |

|||

{{Main|African philosophy|Ancient Egyptian philosophy||Ethiopian philosophy||Ubuntu philosophy|}} |

|||

[[File:DisputeBetweenAManAndHisBa-Soul Photomerge-AltesMuseum-Berlin.png|thumb|300px|Merged photos depicting a copy of the ancient Egyptian papyrus "The Dispute Between a Man and His Ba", written in [[hieratic]] text. Thought to date to the Middle Kingdom, likely the [[Twelfth dynasty of Egypt|12th Dynasty]].]] |

|||

[[File:Zera_Yacob.jpg|thumb|Painting of Zera Yacob from [[Claude Sumner]]'s ''Classical Ethiopian Philosophy'']] |

|||

African philosophy is philosophy produced by [[African people]], philosophy that presents African worldviews, ideas and themes, or philosophy that uses distinct African philosophical methods. Modern African thought has been occupied with [[Ethnophilosophy]], that is, defining the very meaning of African philosophy and its unique characteristics and what it means to be [[African people|African]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Janz|first=Bruce B.|year=2009|url=https://books.google.com/books?isbn=0739136682|title=Philosophy in an African Place|location=Plymouth, UK|publisher=[[Lexington Books]]|pages=74–79}}</ref> |

|||

The philosophical tradition in Africa derived from both ancient Egypt and scholarly texts in [[History of Africa|medieval Africa]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Imbo |first1=Samuel Oluoch |title=An introduction to African philosophy |date=1998 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |location=Lanham, Md. |isbn=0847688410 |page=41}}</ref> |

|||

During the 17th century, [[Ethiopian philosophy]] developed a robust literary tradition as exemplified by [[Zera Yacob (philosopher)|Zera Yacob]]. Another early African philosopher was [[Anton Wilhelm Amo]] ({{c.|1703|lk=no}}–1759) who became a respected philosopher in Germany. Distinct African philosophical ideas include [[Ujamaa]], the [[Bantu peoples in South Africa|Bantu]] idea of [[Bantu Philosophy|'Force']], [[Négritude]], [[Pan-Africanism]] and [[Ubuntu (philosophy)|Ubuntu]]. Contemporary African thought has also seen the development of Professional philosophy and of [[Africana philosophy]], the philosophical literature of the [[African diaspora]] which includes currents such as [[black existentialism]] by [[African-Americans]]. Some modern African thinkers have been influenced by [[Marxism]], [[African-American literature]], [[Critical theory]], [[Critical race theory]], [[Postcolonialism]] and [[African feminism|Feminism]]. |

|||

=== Indigenous American philosophy === |

|||

{{Main|Indigenous American philosophy}} |

|||

[[File:Tlamatini_observe_stars_-_Codex_Mendoza.jpg|thumb|left|A [[Tlamatini]] (Aztec philosopher) observing the stars, from the [[Codex Mendoza]]]] |

|||

[[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Indigenous-American]] philosophical thought consists of a wide variety of beliefs and traditions among different American cultures. Among some of [[Native Americans in the United States|U.S. Native American]] communities, there is a belief in a metaphysical principle called the '[[Great Spirit]]' ([[Siouan languages|Siouan]]: ''[[Wakan Tanka|wakȟáŋ tȟáŋka]]''; [[Algonquian languages|Algonquian]]: [[Gitche Manitou|''gitche manitou'']]). Another widely shared concept was that of ''[[orenda]]'' ('spiritual power'). According to Whiteley (1998), for the Native Americans, "mind is critically informed by transcendental experience (dreams, visions and so on) as well as by reason."<ref name="rep.routledge.com">{{cite book|last=Whiteley|first=Peter M.|year=1998|chapter-url=https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/native-american-philosophy/v-1|chapter=Native American philosophy|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200806154717/https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/native-american-philosophy/v-1|archive-date=6 August 2020|url-status=live|title=Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy|title-link=Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy|publisher=[[Taylor & Francis]]|doi=10.4324/9780415249126-N078-1|isbn=9780415250696 }}</ref> The practices to access these transcendental experiences are termed ''[[shamanism]]''. Another feature of the indigenous American worldviews was their extension of ethics to non-human animals and plants.<ref name="rep.routledge.com"/><ref>{{cite book|last=Pierotti|first=Raymond|year=2003|chapter-url=http://www.se.edu/nas/files/2013/03/5thNAScommunities.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160404090034/http://www.se.edu/nas/files/2013/03/5thNAScommunities.pdf|archive-date=4 April 2016|chapter=Communities as both Ecological and Social entities in Native American thought|title=Native American Symposium ''5''|location=Durant, OK|publisher=[[Southeastern Oklahoma State University]]}}</ref> |

|||

In [[Mesoamerica]], [[Aztec philosophy|Nahua philosophy]] was an intellectual tradition developed by individuals called ''[[tlamatini]]'' ('those who know something')<ref>{{cite book|last1=Portilla|first1=Miguel León|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OI9J7R-R1awC&q=120|title=Use of "Tlamatini" in ''Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Nahuatl Mind – Miguel León Portilla''|year=1990|isbn=9780806122953|access-date=December 12, 2014|archive-date=17 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191217032135/https://books.google.com/books?id=OI9J7R-R1awC&q=120|url-status=live}}</ref> and its ideas are preserved in various [[Aztec codices]] and fragmentary texts. Some of these philosophers are known by name, such as [[Nezahualcoyotl (tlatoani)|Nezahualcoyotl]], [[Aquiauhtzin]], [[Xayacamach]], [[Tochihuitzin coyolchiuhqui]] and Cuauhtencoztli.<ref name=":5">{{cite thesis|author=Leonardo Esteban Figueroa Helland|year=2012|url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/79564237.pdf|title=Indigenous Philosophy and World Politics: Cosmopolitical Contributions from across the Americas|type=PhD dissertation|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211118140515/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/79564237.pdf|archive-date=18 November 2021|url-status=live|publisher=Arizona State University}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{cite journal|last=Maffie|first=James|date=March 2002|url=https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.878.7615&rep=rep1&type=pdf|title=Why Care about Nezahualcoyotl? Veritism and Nahua Philosophy|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211118140518/https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.878.7615&rep=rep1&type=pdf|archive-date=18 November 2021|journal=Philosophy of the Social Sciences|volume=32|number=1|pages=71–91|publisher=Sage Publications|doi=10.1177/004839310203200104 |citeseerx=10.1.1.878.7615 |s2cid=144901245 }}</ref> These authors were also poets and some of their work has survived in the original [[Nahuatl]].<ref name=":5"/><ref name=":1"/> |

|||

Aztec philosophers developed theories of metaphysics, epistemology, values, and aesthetics. Aztec ethics was focused on seeking ''tlamatiliztli'' ('knowledge', 'wisdom') which was based on moderation and balance in all actions as in the [[Nahuas|Nahua]] proverb "the middle good is necessary".<ref name="iep.utm.edu" /> The Nahua worldview posited the concept of an ultimate universal energy or force called ''[[Ōmeteōtl]]'' ('Dual Cosmic Energy') which sought a way to live in balance with a constantly changing, "slippery" world. The theory of ''[[Teotl]]'' can be seen as a form of [[Pantheism]].<ref name="iep.utm.edu">{{cite encyclopedia|title=Aztec Philosophy|encyclopedia=Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy|url=http://www.iep.utm.edu/aztec/|date=|access-date=25 December 2016|archive-date=25 May 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200525172948/https://www.iep.utm.edu/aztec/|url-status=live}}</ref> According to James Maffie, Nahua metaphysics posited that teotl is "a single, vital, dynamic, vivifying, eternally self-generating and self-conceiving as well as self-regenerating and self-reconceiving sacred energy or force".<ref name=":1"/> This force was seen as the all-encompassing life force of the universe and as the universe itself.<ref name=":1"/> |

|||

[[File:Pachacuteckoricancha.jpg|thumb|Depiction of [[Pachacuti]] worshipping [[Inti]] (god Sun) at [[Coricancha]], in the 17th century second chronicles of [[Martín de Murúa]]. Pachacuti was a major Incan ruler, author and poet.]] |

|||

The [[Inca civilization]] also had an elite class of philosopher-scholars termed the ''amawtakuna'' or ''amautas'' who were important in the [[Inca education]] system as teachers of philosophy, theology, astronomy, poetry, law, music, morality and history.<ref name=":2">{{cite journal|last=Yeakel|first=John A.|date=Fall 1983|url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/288024952.pdf|title=Accountant-Historians of the Incas|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211112153051/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/288024952.pdf|archive-date=12 November 2021|url-status=live|journal=Accounting Historians Journal|volume=10|issue=2|pages=39–51 |doi=10.2308/0148-4184.10.2.39 }}</ref><ref name=":3">{{cite book|last1=Adames|first1=Hector Y.|last2=Chavez-Dueñas|first2=Nayeli Y.|year=2016|title=Cultural Foundations and Interventions in Latino/a Mental Health: History, Theory and within Group Differences|pages=20–21|publisher=Routledge}}</ref> Young Inca nobles were educated in these disciplines at the state college of Yacha-huasi in [[Cusco|Cuzco]], where they also learned the art of the [[quipu]].<ref name=":2"/> Incan philosophy (as well as the broader category of Andean thought) held that the universe is animated by a single dynamic life force (sometimes termed ''camaquen'' or ''camac'', as well as ''upani'' and ''amaya'').<ref name=":6">{{cite book|contributor-last=Maffie|contributor-first=James|year=2013|contribution=Pre-Columbian Philosophies|last1=Nuccetelli|first1=Susana|last2=Schutte|first2=Ofelia|last3=Bueno|first3=Otávio|title=A Companion to Latin American Philosophy|publisher=Wiley Blackwell}}</ref> This singular force also arises as a set of dual complementary yet opposite forces.<ref name=":6"/> These "complementary opposites" are called [[yanantin]] and [[Yanantin#Masintin|masintin]]. They are expressed as various polarities or dualities (such as male–female, dark–light, life and death, above and below) which interdependently contribute to the harmonious whole that is the universe through the process of reciprocity and mutual exchange called ''ayni''.<ref>{{cite book|last=Webb|first=Hillary S.|year=2012|title=Yanantin and Masintin in the Andean World: Complementary Dualism in Modern Peru}}</ref><ref name=":6"/> The Inca worldview also included the belief in a [[Creator deity|creator God]] ([[Viracocha]]) and [[reincarnation]].<ref name=":3"/> |

|||

== Branches of philosophy == |

== Branches of philosophy == |

||

| Line 474: | Line 374: | ||

* Bullock, Alan, and Oliver Stallybrass, ''jt. eds''. ''The Harper Dictionary of Modern Thought''. New York: Harper & Row, 1977. xix, 684 p. ''N.B''.: First published in England under the title, "''The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought''". {{ISBN|978-0-06-010578-5}} |

* Bullock, Alan, and Oliver Stallybrass, ''jt. eds''. ''The Harper Dictionary of Modern Thought''. New York: Harper & Row, 1977. xix, 684 p. ''N.B''.: First published in England under the title, "''The Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought''". {{ISBN|978-0-06-010578-5}} |

||

* [[William L. Reese|Reese, W.L.]] ''Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion: Eastern and Western Thought''. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1980. iv, 644 p. {{ISBN|978-0-391-00688-1}} |

* [[William L. Reese|Reese, W.L.]] ''Dictionary of Philosophy and Religion: Eastern and Western Thought''. Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press, 1980. iv, 644 p. {{ISBN|978-0-391-00688-1}} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Adamson |first1=Peter |last2=Taylor |first2=Richard C. |title=The Cambridge Companion to Arabic Philosophy |date=9 December 2004 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-107-49469-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iFMiAwAAQBAJ |language=en |access-date=7 June 2023 |archive-date=7 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230607072853/https://books.google.com/books?id=iFMiAwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite web |last1=Adamson |first1=Peter |title=al-Kindi |url=https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/al-kindi/ |website=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy |publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University |access-date=7 June 2023 |date=2020 |archive-date=21 May 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190521181245/https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/al-kindi/ |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Adamson |first1=Peter |title=Byzantine and Renaissance Philosophy: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, Volume 6 |date=10 February 2022 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-266992-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UmlbEAAAQBAJ |language=en |series=A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps |volume=6 |access-date=25 May 2023 |archive-date=25 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230525075421/https://books.google.com/books?id=UmlbEAAAQBAJ |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Adamson |first1=Peter |last2=Ganeri |first2=Jonardon |title=Classical Indian Philosophy: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, Volume 5 |date=2020 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-885176-9 |pages=101–109 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NCbTDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA101 |language=en}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Adamson |first1=Peter |title=Medieval Philosophy |date=September 2019 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-884240-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hverDwAAQBAJ |language=en |series=A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps |volume=4 |access-date=2023-05-25 |archive-date=2023-05-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230525075421/https://books.google.com/books?id=hverDwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Adamson |first1=Peter |title=Philosophy in the Islamic World |date=2016 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-957749-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KEpRDAAAQBAJ& |language=en |series=A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps |volume=3 |access-date=2023-05-25 |archive-date=2023-05-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230525075423/https://books.google.com/books?id=KEpRDAAAQBAJ& |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Andrea |first1=Alfred J. |last2=Overfield |first2=James H. |title=The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Volume I: To 1500 |date=1 January 2015 |publisher=Cengage Learning |isbn=978-1-305-53746-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=x5-aBAAAQBAJ |language=en |access-date=10 June 2023 |archive-date=22 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230622154153/https://books.google.com/books?id=x5-aBAAAQBAJ |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Anstey |first1=Peter R. |last2=Vanzo |first2=Alberto |title=Experimental Philosophy and the Origins of Empiricism |date=31 January 2023 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-009-03467-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2LytEAAAQBAJ |language=en |access-date=2 June 2023 |archive-date=3 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230603065939/https://books.google.com/books?id=2LytEAAAQBAJ |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Banhatti |first1=G. S. |title=Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda |date=1995 |publisher=Atlantic Publishers & Dist |isbn=978-81-7156-291-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jK5862eV7_EC |language=en }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Beaney |first1=Michael |title=The Oxford Handbook of The History of Analytic Philosophy |date=20 June 2013 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-166266-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eMZoAgAAQBAJ |language=en |access-date=25 May 2023 |archive-date=25 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230525075417/https://books.google.com/books?id=eMZoAgAAQBAJ |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Bilimoria |first1=Puruṣottama |title=History of Indian philosophy |date=2018 |publisher=Routledge |location=Abingdon, Oxon New York (N.Y.) |isbn=978-0-415-30976-9}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Blackson |first1=Thomas A. |title=Ancient Greek Philosophy: From the Presocratics to the Hellenistic Philosophers |date=6 January 2011 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1-4443-9608-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=89zzlbsG1KgC |language=en |access-date=28 May 2023 |archive-date=28 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230528074911/https://books.google.com/books?id=89zzlbsG1KgC |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Boyd |first1=Craig A. |last2=Timpe |first2=Kevin |title=The Virtues: A Very Short Introduction |date=25 March 2021 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-258407-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OIskEAAAQBAJ |language=en |access-date=13 June 2023 |archive-date=22 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230622154156/https://books.google.com/books?id=OIskEAAAQBAJ |url-status=live }} |

|||